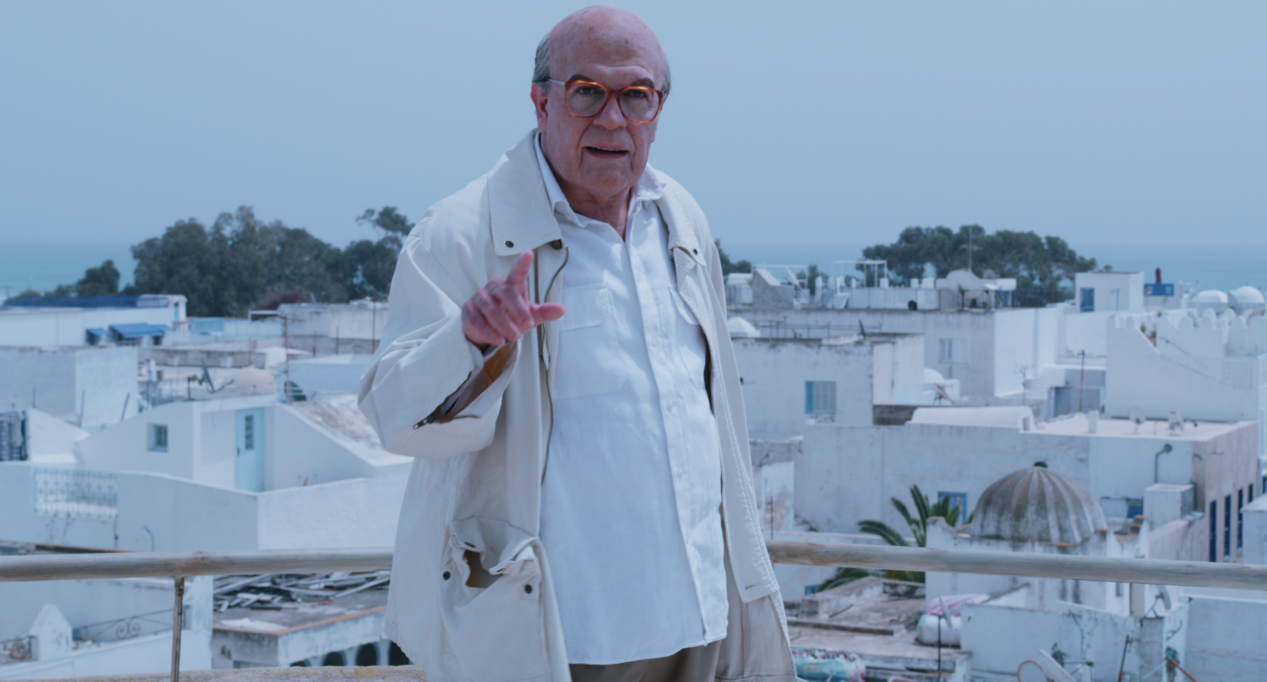

Hammamet, the Last Craxi

“Hammamet,” the new film by Gianni Amelio, tells the story of the final months of the life of socialist leader Bettino Craxi, known in the States for the Crisis of Sigonella, when he refused to give over to the Americans the Palestinian hijakers of the Achille Lauro cruise ship, who were then tried and condemned in Italy. Pierfrancesco Favino transcends all limits in terms of presence, acting abilities and in replicating the voice and movements of the former Prime Minister.

“But it isn’t a biography of Craxi,” as the director claims. “Hammamet is not a partisan film, but the human tale of a man who has reached the apex of power and now has to come to terms with himself and with that feeling of abandonment and solitude that overcomes those who know the end is near. The melodrama aspect imposes itself on the historical revisitation, unfolding the former Prime Minister’s inner struggles. The name of Craxi is never mentioned in the movie.

The truth of the facts is left outside of Hammamet’s villa, stored in judicial archives. The fall of the king is told through the clash with his daughter - Stefania in real life but Anita in the film, the name of Garibaldi’s partner - who wants to fight for him. With politics out of the way, or ruled by exchanges with anonymous politicians in which most things remain unsaid, we are left with an ill man, devoured by rage and by ambiguity towards a country by which he feels abandoned, left alone with his ghosts in a country that could not provide him with the adequate care for his serious ailments. That Italy of which Craxi could only glimpse the coast from the beaches of the Tunisian city where he found refuge in 1994.

Amelio’s “neither exiled, nor fugitive” Craxi appears to gradually lose grasp of reality, crying out his reasons as if they were absolute and absolvent. The director stays clear from providing explanations of why the Secretary of the Italian Socialist Party was involved in the Mani Pulite scandal and condemned twice in Italy. He abstains from making judgements on his way of conducting politics, which remains to this day the topic of heated debates.

He favors an incomplete view of a still highly controversial figure in Italian history, which could turn the noses of both those hoping for some sort of redemption and those who, on the other hand, want an unconditional condemnation. “I made the film I wanted to make,” Amelio concludes “not a propaganda poster.”

The film comes 20 years after the death of the Secretary of the Italian Socialist Party from 1976 to 1993, which took place on January 19, 2000 in his Tunisian home.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.