Italian Youth: On the Hunt for Jobs

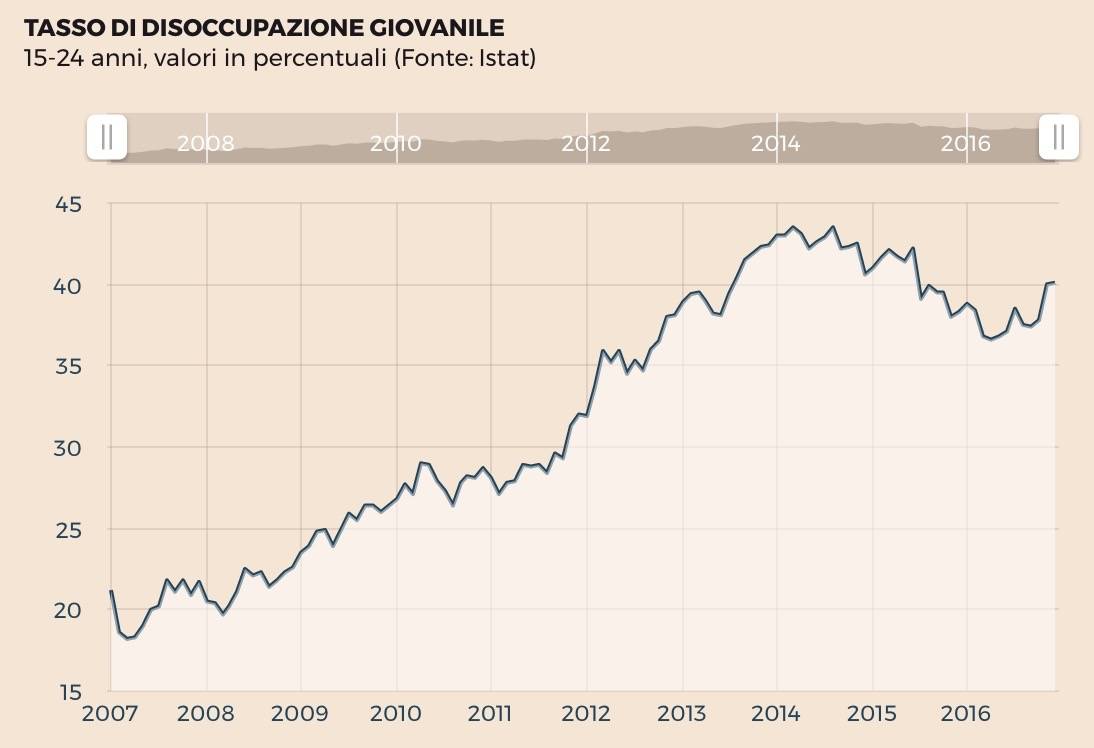

The Italian government was meeting today to discuss a plan to give a helping hand to the vast numbers of jobless or precariously employed Italian youth through concession of a "youth pension." The point would be to compensate for the high rate of youth unemployment, which stands at 40%. This is worse only in Greece (47.3%) and Spain (44.4%), according to European Commission statistics issued in a new, 260-page report, "Employment and social developments in Europe (ESDE)" covering the 28 member countries of the European Union.

"On average, in Italy a person younger than age 30 earns 60% less than those whose are over 60," the report continues. Employment is particularly precarious due to short and badly written contracts which bring terrible insecurity to the young people. As the report also points out, young people with parents (and grandparents) willing and able to support them are bankrolled by the older generations, but this causes "a distortion" in family relations. According to Eurostat, two out of three live at home by comparison with one out of two in the rest of Europe and one out of three in the UK. As a result, a new poll shows that six out of ten have scant hope of achieving their parents' standard of living.

Another distortion comes from the trade unions in Italy, whose membership is made up primarily of those who are pensioners: attend any union organization, and this fact is instantly visible. The left-leaning CGIL, for instance, is composed of 3 million pensioners, or 50% of its membership, whereas in Germany, Austria, Finland and the Low Countries pensioners make up only 15% of the trade union members.

Other studies show that almost 20% of Italy's youth between 15 and 24, or one out of five -- that is, 2.5 million young people -- are classified as NEET: neither working, studying or in training programs. This is double the percentage of young NEETs in the rest of Europe, where the median is 11.5%, and higher than in Greece, Spain or Bulgaria, countries considered less economically secure than Italy.

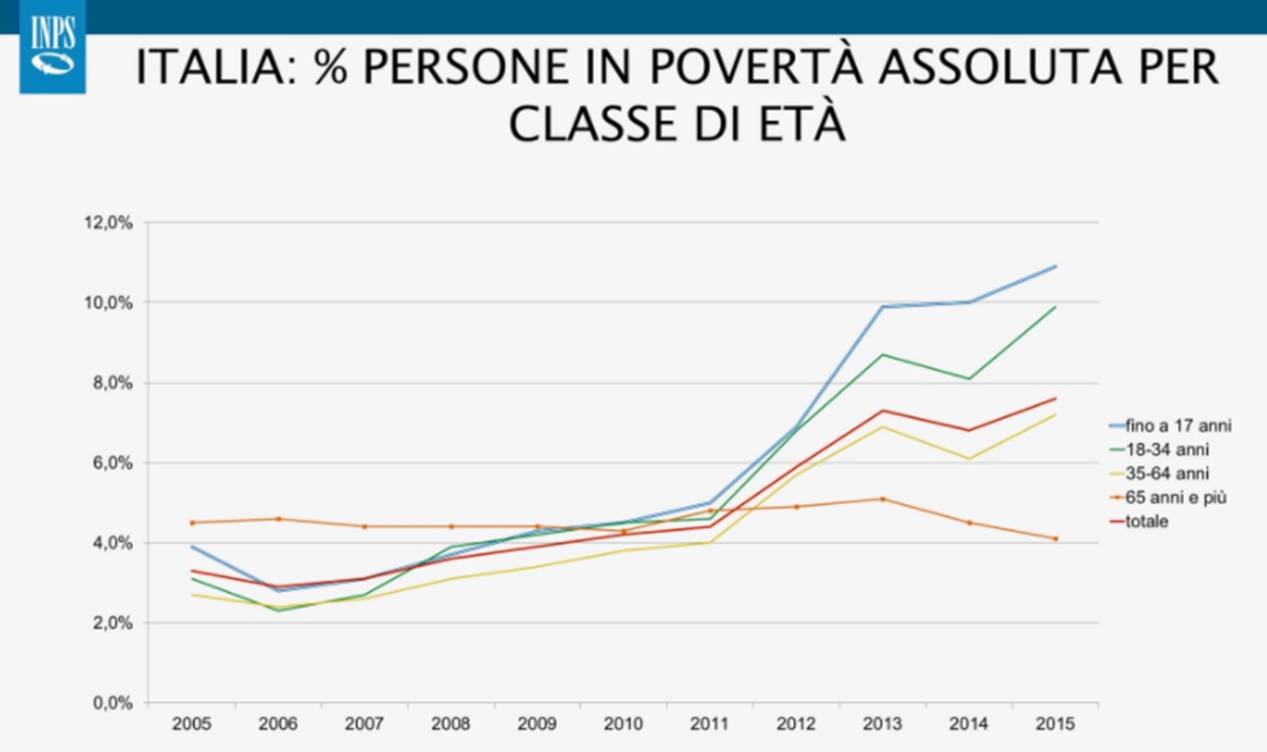

As economist Tito Boeri told the Commission of Constitutional Affairs of the Chamber of Deputies on July 17, "There is a very strong generational problem, in the way our social security [system] is dealing with the problem of youth." Boeri, a graduate of Milan's prestigious Bocconi University and post-graduate studies at New York University, is president of Italy's national social security institute, the Istituto Nazionale Previdenza Sociale (INPS).

Today's cabinet debate is over whether or not to give unemployed youth a subsistance grant, or "youth pension," in the new phrasing. The question is complicated by the varieties of experience and training which young people have: should all have the same "youth pension"? Don't count your youth pension until it is hatched, however. Analysts here say that to concede this is unrealistic at this point -- but realistic in terms of future electioneering.

One out of three Italian young people seek out their own remedy: migration abroad. Over half are from the South of Italy and its islands. Among the migrants is Olivia, 30, born in Rome. She had previously left Italy to work in Spain, but has since moved on to join the 630,000 Italians working in Germany. Visiting her family in Rome this month, she said, "Yes, the work conditions are better there, but it is close enough that I can leave Berlin once a month to come home to see my family."

Olivia is among the 4.2 million Italians living abroad, of whom almost half are female. A report by the Fondazione Migrantes in 2011 showed that Italian emigration was concentrated in Europe (55.8%) and in the U.S. (38.8%). The greatest number of emigres came from Rome itself. Perhaps surprisingly, this isb double the number of emigres from Naples.

On the slightly more positive side, the state statistics agency ISTAT points out that the negative percentages for youth employment also reflect a decline of 2% in the numbers of those between 35 and 49 in just one year, due to the lowered birth rate in their time. The figures tend to be further skewed by the longevity of the older citizens and hence their demographic effects.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.