The Italian Risorgimento Seen by its Women. The Key Roles of Sara Levi and Amelia Pincherle Moravia

The calendar of events surrounding the 150th anniversary of the Italian Unification continues to grow. This time it was Marina Calloni, from the Università Bicocca of Milan to give voice to the events of the Risorgimento. In the library of NYU’s Casa Italiana Zerilli-Marimò, Calloni shed some light on two unjustly forgotten female protagonists of the season: Sara Levi and Amelia Pincherle Moravia.

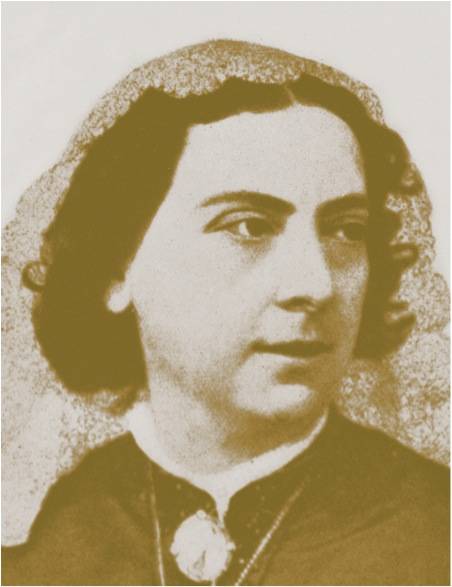

As Jews, they both lived important moments of the unification process of the 19th and 20th centuries: Sara Levi was born in 1819 and died in 1882, while Amelia Pincherle lived from 1870 to 1954. The names of their families are connected: Sara Levi was part of the Rosselli family on her mother’s side and married Moses Nathan, a German who later became a British citizen. Amelia Pincherle Moravia, sister of Carlo Moravia, the father of the famous author Alberto, belonged to a rich Jewish family who had supported the Republic of Venice against the Austrian Empire; she married Joe Rosselli, nephew of Sara Levi, and gave birth to three sons: Aldo, Nello and Carlo. Carlo Rosselli founded the anti-Fascist movement ‘Giustizia e Libertà’ in 1929.

Sara’s political activism was an example for her twelve children, all of which remarkably survived, as Calloni pointed out, considering the infant death rate of the century. Sara brought up her children with the earnings of the Minerary Establishment of Siele, near Mount Amiata, in Tuscany. Investing in the mine was a great intuition, demonstrating an uncommon entrepreneurship. Together with aiding the family, the economic stability helped finance charity work and political campains of the Risorgimento. A true patriot, she supported Mazzini during his exile in London, Lugano and Pisa, playing a key role in the Partito d’Azione. It was in her house in Pisa that Mazzini died, under the pseudonym Mr. Brown. Accused of conspiring, she was forced to seek refuge in Lugano and returned to Italy and Rome only at the end of the unification process, in 1871. Her children also made themselves known for their political commitment: the fifth-born Ernesto became mayor of Rome in 1907; it was the first time a Jewish Republican, an opposer of the Pope’s policies, was elected in a city still quite faithful to the idea of the Pontificial State.

An art devotee, Amelia Pincherle was the first woman to win a prize for a play, in 1898, when she wrote ‘Anima’; tired of his infidelity, in 1902 she divorced her husband, a strong choice for the time. She began a new life as mother of three children, alone, and politically active. At first she was favorable to Italy’s intervention in World War I, but later changed her mind about the Savoia monarchs after Victor Emmanuel III signed the anti-Semitic laws under the Fascist dictatorship.

Amelia, like Hannah Arendt, considered herself a Semite but and anti-Zionist: “I am certainly Jewish, but first of all I am Italian”, she would say.

The war also took the life of her son Aldo in 1916 at the Carnia front. Nello and Carlo were exiled for their opposition to Fascism and were assassinated in 1937. Destroyed by the death of her sons, Amelia exiled herself in Switzerland, England and the United States. She made up her mind to return to Italy only when it would become a free and republican country. In an article published during her time in America, she wrote: “Today I see the same problems in Italy; we need concrete action, diversified and with a new mentality”. Amelia returned to Italy in 1946.

In her presentation, Marina Calloni underlined how both these women belonged to the liberal, secular and Jewish tradition of the Italian political agenda, while at the same time representing two examples of female emancipation. The role of women in the Risorgimento and Mazzini’s agenda on female emancipation were the main topics of the discussion that followed the lecture, proof of the fact that speaking about women and politics isn’t always easy, and certainly not frequent.

Marina Calloni concluded: “To learn more about the life and thoughts of Sara and Amelia allows us to approach the analysis of the Risorgimento from a different point of view, the prospective of women; this said, their thought was characterized by always being original and free”.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.