Ferramonti, 70 Years After the Liberation

Like many difficult memories, the history of Ferramonti and Fascist internment continues to elude the public conscience and current discourse on Italy’s totalitarian past. Yet, over the last two decades, a remarkable series of studies has exposed the practice of segregation of “undesirable civilians”. This chapter of Italy’s history is not only an integral part of the vicissitudes of 20th Century Europe, but concerns our present and the ways in which our society represents dissent and acts upon and represents the dynamics between dominant, subordinate and transversal groups.

While publications and detailed archival resources have become more widely available to scholars and the public, the absolving narrative of the “good camps” where Jews survived in high percentage persists, perpetuating the improbable concept of Italian exceptionalism and a reading of Fascism as far removed from any European and colonial context.

The public narrative on Ferramonti is based on two powerful rhetorical devices: the assertion of a cause-and-effect relationship between the survival of Jews in the camp and the fact that Jewish internees and Calabrian villagers engaged in material and personal exchanges; and a misleading comparison between the Ferramonti and Auschwitz – which immediately preclude any genuine analysis of history of Italian internment.

The recent renovation of the barracks at Ferramonti into a Club-Med-style creation in warm yellow tones and the public relations campaign promoting been Calabria as a “safe haven,” and “Southern paradise” for Jewish refugees, have met with frank perplexity by historians, public intellectuals and landmark organizations including Italia Nostra.

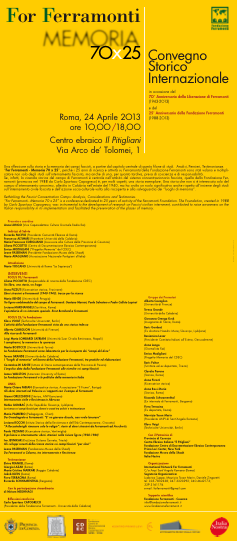

The upcoming conference to be held at the prestigious Jewish center il Pitigliani in Rome marking the 70th anniversary of the liberation of the camp at Ferramonti and honoring 25 years of the Ferramonti Foundation, offers a significant opportunity to reflect on the status of current research and discuss the work that still remains to be done. The publication of its minutes will provide an indispensable tool for reevaluating the history of Ferramonti within the international context to which it belongs.

The conference is organized through the combined efforts of scholars and families of former internees and is sponsored by such leading lights as Anna Rossi Doria, Claudio Pavone, Piero Terracina, Anna Longo and Riccardo Schwamenthal, among others.

Speakers will include: Carlo Spartaco Capogreco, whose 1988 groundbreaking volume on fascist internment has become a reference for all scholars in the field, Klaus Voigt, Liliana Picciotto, Mario Rende, Anna Pizzuti, Luciana Mariangeli, Alberto Cavaglion, Teresa Grande, James Walston, Enrico Modigliani, Mario Toscano, Luciana Rocchi and Metka Gombač.

The concentration camp at Ferramonti - originally named “Media Valle Crati”, for its setting - became operational on June 20th, 1940 with the stated purpose of removing from society “enemy aliens, subjects dangerous to national security and foreign Jews from countries that practiced racial persecution”.

Ferramonti was located on a malaria-plagued piece of land, about 20 miles from Cosenza in Calabria, and was described, in a report from the Public Health Department, as “unhealthy and inhospitable”.

Its construction and management were entrusted to the Fascist entrepreneur Eugenio Parrini, whose company had - within days of the internment decree - acquired control of the development contracts for this and other fascist camps.

The Ministry of the Interior appointed the police officer Paolo Salvatore (1899-1980) as camp director. Salvatore was from Avellino and had been previously employed at the notoriously brutal political detention facility of Ponza. The camp’s staff included a secretary, a typist and two motorcyclists.

Upon arrival, the internees underwent bureaucratic formalities, and were assigned to their barracks. Each received two trestles and a plank to be used as bed, a mattress, a pillow, two blankets, two sheets and a towel.

The internees were subject to heavy restrictions in all aspects of their lives. Initially, any form of assembly including teaching and praying was forbidden. The distribution of quinine - essential to the treatment of malaria - was also prohibited This measure was later amended, but is indicative of the authorities’ ambivalence towards their charges and the welfare of the internees. Detainees were also subject to daily roll-calls and patrol-towers were located along the external fence.

The establishment of the internment camps initially generated local business and was welcomed by local authorities. However, the arrival of the Jewish internees posed new challenges to the small police staff of this remote Southern village.

Ferramonti di Tarsia was in fact even further South than Eboli, that site of political confinement so insightfully immortalized in Carlo Levi’s Christ Stopped at Eboli.

Unlike the local population, oppressed and disenfranchised by a Regime that, at best, considered them a resource for manning the Spanish and Soviet fronts, the internees were, by and large, educated, worldly and vocal. They represented an unprecedented and probably unfathomable form of opposition. Their requests, recorded in thousands of letters and petitions preserved in the Italian State Archives, were non-political, non-violent, and related to matters of health, family reunions, children’s schooling and food and clothing – issues that had hardly been a police concern before July 1940. The supplicants were articulate, accommodating and even flattering toward any authority that might listen to them and perhaps - if not act – then at least answer.

Thousands of missives written between July 1940 and July 1943, record one consistent and universal desire - to be relocated to other, less harsh, internment locations. No one wanted to go to or remain in Ferramonti. No one could have imagined at that point that the Allies would land in Italy in July of 1943 and that internment in Ferramonti would save their lives.

Local police and the powers that be were thrown by the incessant flow of petitions and initiatives by the internees, which opened the door to persons or organizations who might act as mediators for this foreign body which, in their views, threatened the public order.

The Italian Jewish relief agency Delasem, immediately identified Ferramonti as a high-priority area. It began to support the internees with subsidies, books, food and liturgical material and set up an infrastructure for the children. A soup kitchen and a school were established and maintained through the indefatigable efforts of Israel Kalk, a Latvian Jew who had become Italian before 1919 and had therefore been able to retain his Italian citizenship.

Delasem operated in close collaboration with the Joint Distribution Committee from which it received substantial support. The Joint created an English language media watch for the fascist camps. Starting in 1938 reports on Mussolini’s treatment of foreign Jews was circulated through the Jewish Telegraphic Agency as well as diplomatic channels. The sudden arrest of thousands of foreign Jews in 1940 brought the otherwise discreetly handled question of fascist civilian internment into the international spotlight, and the danger its potentially negative impact posed for the image of the fascist regime among Americans and Italian Americans, played an undeniable role in shaping the attitude and tone of the Italian authorities towards foreign Jews.

The Vatican too, that had looked favorably on the establishment of Jewish internment, deployed clergy and small charity funds to many of the internment locations. In 1941, the 65-years old Capuchin Fraire Callisto Lapinot (1876-1966), a native of Alsace, was sent to Ferramonti, ostensibly to assist Catholic internees but also - as revealed by his diary – to encourage and support new converts.

In 1942, Riccardo Pacifici Chief Rabbi of Genoa and member of Delasem, also travelled to Ferramonti to bring comfort to his coreligionists and assess their conditions and needs.

In spite of the potentially divergent goals of Father Lapinot and Delasem, the necessities of physical survival and the common needs of internees and local villagers in the face of hunger and illness frequently prevailed, facilitating a wide range of cooperative endeavors.

These developments led to some restrictions – especially those limiting public assembly, praying and teaching - being progressively lifted; and soon afterwards local authorities decided to allow the creation of a committee of Jewish internees that could help with the management of community and religious issues. The creation of this council of internees and of a system of self-governance proved to be the best solution for assuaging anxiety and also provided an essential link between the police authority and more than 2,000 detainees of all ages, languages, genders and backgrounds. In this regard Ferramonti, and the specific characteristics of its location and purpose, repeated the model of other historic cases of segregation of the Jews, such as the ghettos in Papal Rome or occupied Warsaw.

Ferramonti was kept under surveillance internally by volunteer fascist militia (black shirts) – and externally by the National Security Guards. Barring a few isolated cases of violence against internees by the militia, and several documented cases of forced indoctrination, the authorities’ attitude - starting with the amicable marshal Gaetano Marrari, - was generally tolerant and adhered to those regulations outlined by the Geneva Convention in 1929.

From November 1942 other groups of “enemy aliens” would join the Jews at Ferramonti: former Yugoslav, Greek, Chinese and French undesirables, and even, in 1943, a small group of Italian anti-Fascists; but the Jewish presence there never fell below 70%.

In some circumstances, internees were allowed to leave the camp under police surveillance and came into contact with the local population – reduced by the war to mainly women, children and the elderly. Locals were astonished to discover that these “real Jews” bore no resemblance to the dangerous and demonized characters they’d seen depicted in the Italian press since the promulgation of the Racial Laws – in fact no Jews had been in the region since Inquisition times. And so these encounters with detainees, who turned out to be anything but sinister, quickly softened the effects of anti-Semitic propaganda.

By the spring of 1942 the impending defeat of the Axis armies became clear. Over 16,000 foreigners (about 9,000 of them Jewish) were held in Italian detention camps in various locations, and were regarded as an added burden on a country already deep in financial crisis. Government subsidies for food, clothing, housing and medicine quickly decreased. The influx of funds from the Joint Committee now became essential – and not merely for the benefit of Jewish internees.

With the arrival of winter, hunger and malnutrition began to rage at Ferramonti. The Jewish detainees were entrepreneurial and skilled in many fields and the villagers had access to the limited produce still farmed in the area. As the situation at the camp worsened, barter and exchanges with the villagers increased. Soon a black market and various cooperative networks flourished.

By the beginning of the summer 1943, the Fascist Ministry of the Interior was planning to relocate the roughly 2,000 internees of Ferramonti north to Brenner, at the Austrian border. Had this proposal gone forward it would have meant a death sentence. On July 25th however, the King of Italy and the Fascist Council deposed Mussolini and opened the negotiations with the Allies that would lead in the first week of September to the Armistice.

Shortly thereafter, the camp became directly involved in the conflict: on August 27th a Canadian plane flew over the area and bombed Ferramonti causing the death of four internees, wounding eleven and setting two of the barracks on fire. After this painful event, many internees sought shelter in the surrounding hills. Local authorities understood that they would soon come under Allied rule and they relinquished control of the camp. The Parrini management vanished overnight. Left unattended, many barracks were sacked.

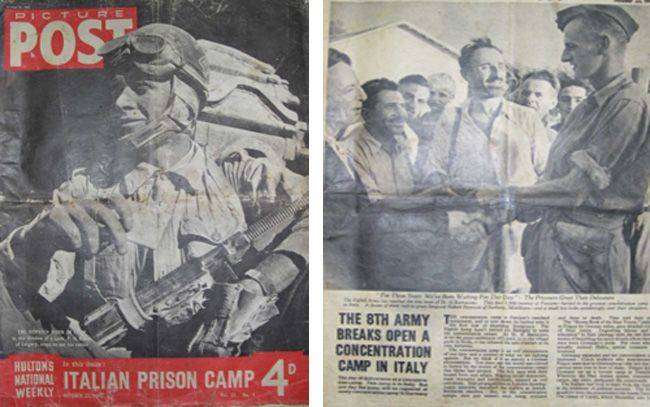

On September 14th, 1943, when more than half of the internees had fled to the surrounding areas, the Eighth battalion of the British Army entered the camp Ferramonti. All internees were set free.

It isn’t difficult to imagine how different their fate would have been, had the Allied forces not advanced so quickly from Sicily, and had Calabria been incorporated into the Italian social Republic.

The Allied army dismantled the bureaucratic structures of the Fascist camp (the “first Ferramonti”) and established a displaced persons camp under the auspices of the Welfare Commission of the Allied Military government in the Occupied Territories. The “second Ferramonti,” under Anglo-American control, was born.

Starting on September 1943, the Welfare Commission appointed Ernest F.Witte as comptroller of Ferramonti. On November 18th, he was replaced by Captain Louis Korn. Camp records document the presence of 1854 people living as displaced persons in Ferramonti.

Between September 1943 and the end of 1944, Ferramonti was home to one of the largest and most active Jewish communities in liberated Italy. It was at this point that that fragile Jewish self-governance that first took shape during manner internment, quickly developed into vital infrastructure, including the setting up all of social and cultural services, media, education, achsharot, small businesses and, above all, a social fabric within which free individuals could return to building their present and future.

From the second Ferramonti, many moved towards other DP camps located in better areas, especially in Puglia and Sicily. Others found their way to Africa, Palestine and the United States of America.

On May 26th, 1944, 254 former internees left Ferramonti for Palestine on the first emigration transport authorized by the British mandatory government. On July 17th, 1944 a little over 1,000 Jews from Ferramonti and other camps in Southern Italy set sail from Naples for the United States.

By the end of the Second World War the facility at Ferramonti had been abandoned. In the following decades its memory was kept alive solely through former internees and their families, and by some local residents

It was not until the beginning of the 1980s with the work of Carlo Spartaco Capogreco, Klaus Voigt, Mario Rende, Francesco Folino, Michele Sarfatti and, later, Anna Pizzuti, that the memory of Ferramonti was summoned back to the arena of history. Inevitably, it began to clash with assorted political narratives and became a territory of contention.

Even to date, in spite of thriving historical research on Fascist internment and on Ferramonti itself, the two distinct chapters in the history of Ferramonti are still packaged together and assessed as such not merely in the memory of some individuals and communities, but also in the public domain of historical record and testimony.

Under the simplistic definitions of “kibbutz camp” and the “anti-Auschwitz”, a complex history of oppression, collusion, cooperation and survival is forgotten along with the barbed wire that once fenced Ferramonti’s 800 acres.

Thanks to Centro Primo Levi NY

======

April 24 | 10 am to 6 pm

Centro Ebraico Il Pitigliani | Via Arco de’ Tolomei, 1, Roma

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.