Another Sicily

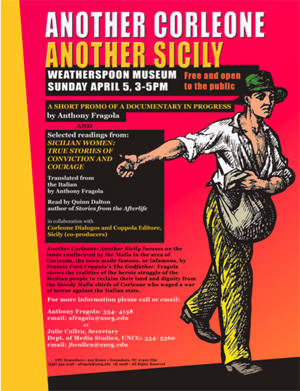

Both Hollywood and European cinema have produced countless films about La Cosa Nostra, the Sicilian Mafia. But Anthony Fragola wants to tell another kind of story, not about the Mafia itself but about the Sicilians dedicated to fighting it. Fragola, a Sicilian American who is a professor of film studies at the University of North Carolina, Greensboro, has completed one documentary film, Un Bellissimo Ricordo (A Beautiful Memory), focusing on Felicia Impastato, the mother of the assassinated anti-Mafia activist Giuseppe “Peppino” Impastato. (Impastato was the subject of director Marco Tullio Giordano’s acclaimed 2000 feature film, I Cento Passi.) Anthony Fragola’s latest documentary is Another Corleone: Another Sicily. The film, a work in progress, examines the anti-Mafia struggle of citizens and activists in the town indelibly linked to the Mafia by The Godfather. In addition to being a filmmaker, Fragola is an author. His short story collection Feast of the Dead (Guernica, 1998) explores Sicilian immigration, culture, and identity. I recently spoke with Professor Fragola about his films, the anti-Mafia movement in Sicily, and his personal commitment to documenting and supporting that movement.

You have made two documentary films, Un Bellissimo Ricordo, and Another Corleone: Another Sicily, both dealing with la lotta alla Mafia, the anti-Mafia struggle in Sicily. What motivated you to make these films?

I began Un Bellissimo Ricordo because of an interview I read with Felicia Impastato in Donne Siciliane: Quindici storie vere (Sicilian Women: Fifteen True Stories), a book by Giacomo Pilati, published by Coppola Editore in Sicily. I was immediately struck by the courage and resiliency of all those women, and especially that of Felicia Impastato, whose son, Peppino was killed by the Mafia because of his open rebellion against it. What struck me was Felicia's courage, her relentless dedication to bring justice to her son's name, and her transcendent spirit in the face of desolation and isolation.

We say, "one thing leads to another," but I prefer the literal translation of the Italian, “Da cosa nasce cosa,” “one thing is born from another.” The Italian expression seems more creative, more of a wholistic natural process and cycle.

On a subsequent trip to Sicily, Salvatore Coppola [of Coppola Editore] took me to the cooperatives in the provinces of Palermo and Trapani. I have always been interested in land and sustainable farming, and I had read that in Sicily there were cooperatives set up on land the government had seized from the Mafia. The cooperatives were attempting to turn these properties into productive, self-sustainable, organic ventures that paid honest wages to the workers. What interested me was the story of the cooperatives and their struggle to be viable. But in order to understand them I had to first learn about the Mafia, especially under the brutal leadership of the Corleonesi, Luciano Liggio, Totò Riina, and Bernardo Provenzano, who waged a merciless terrorist war against the Italian state, killing magistrates, carabinieri, policemen, businessmen, innocent bystanders -- anyone who stood in their way to absolute power.

In order to make a documentary, I needed to see what films had been made, study more about the history of the Mafia and the cooperatives, politics, economics - in short, I felt the need to understand this story in its full complexity. My model for this type of research is the Italian director, Francesco Rosi, whose political films are not well known in this country and are sadly underrated.

Was it difficult to get people like Felicia Impastato, her surviving son Giovanni, and others to speak with you and to allow you to film them? Or were they eager to tell their stories?

Both Giovanni and Felicia were very willing to share their story, not just with me, but with the world. Felicia told me that people from all over Italy and the rest of the world came to see them and that their house [in the western Sicilian town of Cinisi] was always open to visitors. Their home has now been turned into Casa Memoria where the work of promoting legality, civic consciousness, and the fight against the Mafia continues.

In the biopic I Cento Passi, about Peppino, his younger brother Giovanni is depicted as an ordinary youth frightened by Peppino’s intense commitment and his boldness. But in the decades since Peppino’s murder, Giovanni has taken on the mantle of anti-Mafia activist. Does he see himself as continuing his brother’s work?

Giovanni has characterized himself much as he was depicted in the film. After his brother's death, Giovanni found the strength and courage to continue from his brother's spirit. Last year marked the 30th anniversary of Peppino's death, and Giovanni organized a national day of remembrance in Peppino's honor. More than 5000 people attended, and [Sicilian singer-songwriter] Carmen Consoli gave performance in Cinisi. As Salvatore Coppola said, Giovanni is no longer Peppino's brother. Peppino was Giovanni's brother. The banner has been entrusted to Giovanni, who rightly deserves it.

What do people involved in the anti-Mafia movement want the outside world to know about their struggle, and about Sicily today?

First, I would say that they want the world to know that there is a strong anti-Mafia movement in Sicily, that Sicily is NOT the Mafia. The movement is gaining momentum, and there have been triumphs, such as the production of the new wine, I Cento Passi, from the Cooperative Placido Rizzotto. As Luigi Lo Cascio, the actor who played Peppino Impastato, stated at the public presentation of the wine at Giovanni's pizzeria in Cinisi, “Every time you uncork a bottle of this wine it's like firing a bullet against the Mafia.”

Another Corleone: Another Sicily looks at the efforts of the national organization Libera to transform property formerly owned by Mafiosi into agricultural collectives with a social mission. A few years ago I visited the Cooperativa Sociale Placido Rizzotto, in San Giuseppe Jato. I felt that although the coop was a noble undertaking, it also seemed very fragile to me. What’s your assessment of the viability of these projects?

As one of the professional associates working with that cooperative said to me last summer, “we are making steps, but they are slow.” But this month there was an event that demonstrated tremendous strides in the viability of the cooperatives. On March 12, the Bottega di Sapori e Legalità opened in Palermo to sell products from the cooperatives. The event heralded the combination of the forces of law and order, business, Libera, the cooperatives, and the citizens supporting La Bottega. My idea is to become a conduit for these products in the US. At this point I do not know if their production is sufficient for export, but it is one of the many aspects I plan to investigate this summer when I return to shoot more footage for Another Corleone: Another Sicily.

What do you think it will take for “another Corleone, another Sicily” to flourish? And is it realistic to believe that the mafia can be defeated?

It will take the combined effort of every aspect of society -- ordinary citizens, the government's commitment to help the cooperatives, support of investigative magistrates and the judicial system, the clamping down on ‘il pizzo’ [the “protection” money extorted from businesses by the Mafia] and ending the Mafia’s control over government contracts. Also, support for the cooperatives by purchasing their products. Support from Italian Americans and Italian American organizations would also be of tremendous help, not just financial, but moral support as well. And there needs to be a change in the misguided glorification of the Mafia as depicted in The Godfather. That is why I chose the title for my documentary, Another Corleone: Another Sicily.

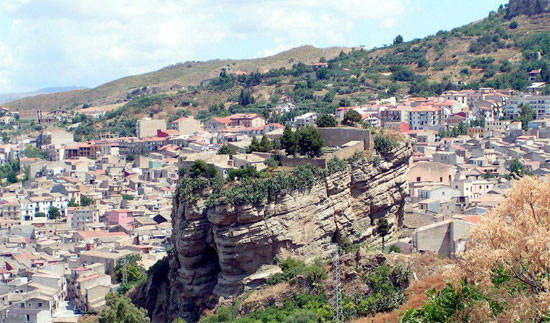

For example, Corleonedialogos.it is advocating a new type of tourism in Corleone, a socially responsible tourism. There are now Mafia tours of the region. People get on a bus, see where The Godfather was purportedly filmed, have lunch, get back on the bus and leave. This other type of tourism wants to take people to the places where activists such as Placido Rizzotto, who was killed for organizing the peasants, was abducted. They also want to show the positive aspects of the village. I, along with the others, was shamefully uninformed. I did not know, for example, that there is an anti-Mafia museum in Corleone that houses the more than 1000 documents that [anti-Mafia prosecutors] Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino prepared for the maxi-trials. [More than 300 mafiosi were convicted in the late 1980s in the Palermo trials.] But the museum lacks funds and may be closed. Italian Americans could show solidarity with the anti-Mafia movement by supporting the museum, the cooperatives, responsible tourism, and other ventures.

You are a Sicilian American committed to documenting the efforts of Sicilians to bring about progressive social change on the island. What’s the source of your “impegno,” your personal commitment?

Good question. Several years ago I was in Sicily to do more literary and film work. Nothing seemed to be going right. I felt isolated and unsupported. I felt I had lived a romanticized illusion, a myth of Sicily, and I doubted I would ever return to continue my work there. Gradually, through a series of events, including encouragement from Professor Antonio Vitti, who was then head of the Italian Department at Wake Forest University, I resumed my work, which led to A Beautiful Memory.

Several years later [author] Giacomo Pilati asked me why I continued this work if I had lost my romantic illusions about Sicily. I can't answer that rationally. I can only say that it is in my blood. Because I was raised, in part, by my Sicilian grandmother, I felt deeply connected to Sicily even as a child. I believe it may be akin to William Blake's “Songs of Innocence and Experience.” Perhaps I see Sicily in a more realistic, but much deeper way. I hope so. I can only say that after many years of working in isolation I have found my calling.

Do you intend to continue making documentaries about Sicily? What are your upcoming projects?

We shall see if I get the support in Sicily I need to do this. So far, I have made extensive contacts, and I am optimistic. I have a rough cut of a documentary about Margherita Asta, whose mother and young twin brothers were killed in a bomb blast intended for an investigative magistrate in Trapani. I want to finish that. I love fables and myths, and Sicily abounds with those. I have recently proposed an idea for a conference and a book on Francesco Rosi that I am excited about. Rosi's films are intelligent, complex investigations into the multiple realities, ambiguities, and paradoxes of Sicilian life, and he and his work deserve to be better known.

And then there are other, more congenial possibilities. I am considering taking small groups on gastronomical tours of Sicily, staying at agriturismi [farm inns] that offer organic food grown and prepared on the premises. I am also communicating with the University of Catania about establishing a collaborative venture with UNC Greensboro, my home institution. You could live forever and never mine all the riches that Sicily has to offer. Maybe therein lies the source of my commitment.

For inquiries about Anthony Fragola’s films, e-mail him at [email protected]

For more information about anti-Mafia Corleone, see Dialogos, http://www.corleonedialogos.it/

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.