On the Disassembly Line at Fiat: A General Strike in the Works?

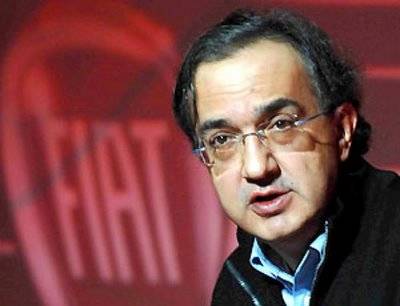

ROME –Both sides, Fiat management and a hard core of recalcitrant labor leaders, are claiming they won in a two-day referendum over a tough new contract. The controversial contract had been hammered out by Sergio Marchionne, the suave and savvy Italo-Canadian who has been running the historic manufacturing company for seven years. In exchange for signing the contract Marchionne promised an unspecified investment in the Turin plant of E 1 billion, and production of new models at a time when European auto sales are beginning to pick up. Besides the 5,500 Fiat workers, the new contract is expected to impact another 10,000 employed in associated industries in and around Turin. Observers here also consider the deal a bell weather for future contracts involving working conditions and salaries for as many as 50,000 factory workers in Italy. While accepted by four smaller and fairly conservative unions (including one of white collar workers), the contract has been bitterly opposed by the left-leaning metal workers union FIOM, part of the powerful CGIL national union, already threatening a general strike and calling for its renegotiation.

At least in theory, FIOM lost, and Marchionne won hands down with 54% of the vote. The turnout, moreover, was of 94% of the circa 5,500 eligible voters (their average age: 48). Visibly relieved, Marchionne praised the vote as “courageous” and “historic,” representing “the desire to take action against being resigned to decline.”

In the background in Turin, besides a few nasty graffiti signed by self-styled Red Brigades, was a European Communist party protest against the “slave conditions” in the contract. This is overstatement, but the new contract is such that, while white collar workers may find it tolerable, its conditions are tough for the assembly line workers.

And in fact, the 441 white collar staffers and supervisors made the difference; if solely blue collar workers had been counted, the referendum would have squeaked through, but by a mere nine votes.

The FIOM protest is over assembly-line conditions, beginning with an eight-hour work day that allows precisely three ten-minute breaks for bathroom calls and coffee, and another thirty minutes for lunch. There will be double and triple turns; plenty of six-day work weeks; no absences for illness near holidays; 120 hours of obligatory overtime—and, as punishment for refusing to sign the contract in the first place, no representation for FIOM delegates. Indeed, some labor experts say the new contract will actually reduce productivity because workers under this degree of stress simply cannot perform well.

Already Marchionne has announced that within this year he will shut down Fiat’s assembly line at Termini Imerese in Sicily, which employs 1,800. Speaking with a journalist some time ago he said that each automobile turned out there cost E 1,000 ($1,300) more than any produced in the Turin plant. Moreover, because the plant was situated close to the sea, parts rusted prematurely.

The Turin workers knew that the stakes were similarly high, for Marchionne’s alternative was to move the Fiat production plant at Mirafiori right out of Italy and into Serbia, where workers earned half as much, and where the government invested in rebuilding the war-damaged plant. This is why the various unions themselves split, quarreling angrily among themselves to the point that one old Fiat hand was shown on Italian TV weeping his heart out. The newcomer pop star politician Nichi Vendola, governor of the Puglia region, who made the pilgrimage to the Mirafiori plant earlier this week, declared, “A referendum like this is a dog’s dinner (una porcata) because it means voting between survival and being thrown onto the street.”

When Italian Premier Silvio Berlusconi made clear his support for Marchionne’s position, Susanna Camusso, the leader of Italy’s largest trade union, CGIL, to which FIOM is allied, said angrily, “The premier and Marchionne are fighting to see who can deliver the greater damage to our country.”

Curiously, in the course of the months-long dispute over the terms of the new contract, Marchionne bolted from the Italian national manufacturers’ association Confindustria. This loss of its preeminent member was a slap in the face for its president Emma Marcigaglia, but then she went on to defend Marchionne’s position anyway. One reason for her supporting her defiant bolter: as Confindustria itself has complained, Italian industrial production has been “bad since 1997.” According to an end-of-year report by the association’s research center, the Centro studi Confindustria, the number of jobless doubled between April 2007 and October 2010, with Italy losing 540,000 jobs between the beginning of the current recession in the first quarter of 2008 and the third quarter of 2010. The report goes on to say that in 2011 “the number of those employed will continue to diminish in 2011 by an estimated 0.4%,” bringing unemployment to 9% by January 1. (The current Economist agrees, putting Italy’s unemployment rate at just under 9%.)

Over the same period Italy’s GDP shrank by 6.8%, despite a more recent upward boost of 1.5% more recently. “It would take us till 2010 to return to the growth levels of the period 2000-2007,” but to achieve this would require emulating German industrial production, concludes the report, which resulted in a 3.5% hike in GDP in 2010, as compared with 1.1% for the same period for Italy, and unemployment at 7.5% as compared with Italy’s 8.6%. However, the Confindustria goes on to say, with a dig at Premier Silvio Berlusconi’s government, “the available tools are inadequate.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.