The Accademia della Crusca [2] (Crusca Academy), literally translates to “The Bran Academy”, was founded in Florence between 1582 and 1583. Its name holds an important significance to its mission. “Crusca” means bran and bran is the portion of the wheat that is discarded when the grain is being cleaned. In essence, the Crusca Academy works to “clean up” the Italian language like is done with the bran in wheat.

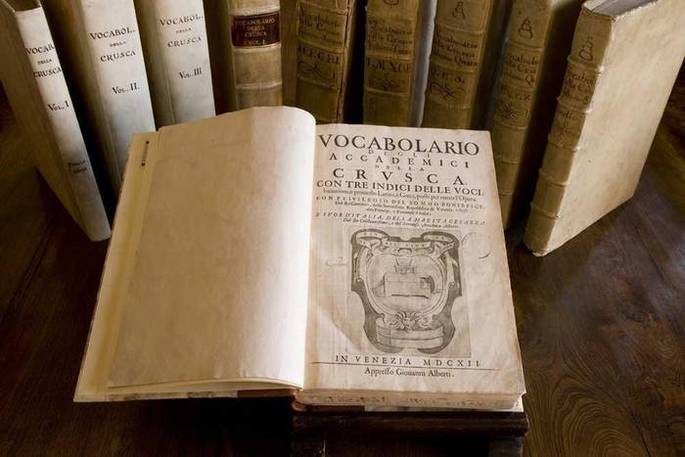

The most fundamental of its accomplishments include the creation of the “Vocabolario” (their official Italian dictionary) in 1612; it became a model dictionary for other European countries. The Crusca Academy is a leading institution in the field of research of the Italian language that concentrates on many aspects of the Italian language, including acquiring and spreading the historical roots and evolution of the Italian language in different areas of Italian society, particularly in schools.

Crusca Academy President Claudio Marazzini had much to say at a conference on the defense of the language this Monday. He also said, “The reasons why Italy is so disposed to foreign influence is the frequent lack of a good knowledge of its own history and language to the extent that would restore belonging to the national culture.”

Language can be seen as the glue of a culture that binds people together—people could come from vastly different parts of a country, with vastly different backgrounds, but when they speak the same language they can still share a common bond. Many, like Marazzini, see anglicisms as a threat because many utilize an English word that has been integrated into their native language when a word for what they want to say already exists in their native language.

He continues, adding, “With this basis and root, young people are easily prone to break off from the national reality and cut their bridges, the few that remain.”

Merriam-Webster defines anglicism as “a characteristic feature of English occurring in another language.” The increasingly pervasive nature of anglicisms in languages, such as Italian, have many worried, like Marazzini, of a loss of their native culture.

The infiltration of English into the Italian language could be for different reasons, however, having English as one of the two official languages of the European Union could certainly play a role. Knowing English helps to unite the European Union since it is often the second language students are taught at European schools. English is widely known and spoken in European countries so it is understandable to see how anglicisms could have developed in the Italian language.

One common anglicism used in the Italian language is “fare lo shopping”. It has the same meaning as in English—to go shopping—however, there is an Italian expression for the same activity, “andare per negozi”. This is likely one of the many examples that Marazzini could consider a reason why Italians don’t love their language—because they have an Italian word to express an action or activity and yet choose to use an English word.

Marazzini’s declaration of “Italian is not a language really loved by the Italians” is provocative, but it is a clear demonstration of his passion to preserve the Italian language.

Source URL: http://newsite.iitaly.org/magazine/focus/facts-stories/article/growing-anglicisms-italians-dont-really-love-their-language

Links

[1] http://newsite.iitaly.org/files/crusca1424842992jpg

[2] http://www.accademiadellacrusca.it/en/pagina-d-entrata