Some of the breads that will be put on the St. Joseph's Tables in Watts

(photos courtesy of Luisa Del Giudice)

The tables and altars constructed for St. Joseph are common among various (Southern) Italian traditions and within the Italian diaspora are examples of some of the ways Italian immigrants put into practice that which suits their hybrid identity as migrants. As Luisa Del Giudice puts it: “It does not take a long stretch of the imagination to see a strong identification of immigrants with Joseph—himself ‘emigrant’—fleeing into Egypt, a stranger in a strange land, at the mercy of a foreign and historically hostile people who had enslaved the Jews” [“

Rituals of Charity and Abundance: Sicilian St. Joseph’s Tables and Feeding the Poor in Los Angeles [3]," California Italian Studies Journal 1(2)].

Set in the multi-racial and culturally dynamic neighborhood of Watts, with

Sabato Rodia’s Nuestro Pueblo [4] in view, The Communal Tables also mark, for me, another section of a decidedly Italian-Californian cartography.

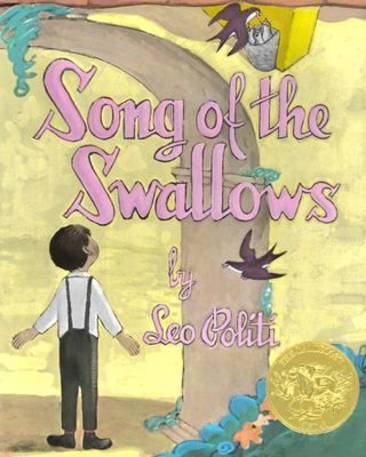

The reshaping of a St. Joseph’s Day Italian immigrant experience within a multi-cultural, Southern California landscape also figures in the children’s picture book, Song of the Swallows, published by

Leo Politi [5] in 1948. (Indeed, Politi’s art and the Watts Towers are

certainly no strangers [6]in other ways as well, but I digress.)

The children’s book tells the “legend” of the famous Capistrano Mission swallows, las golondrinas, who magically fly back from South America and arrive just in time for Saint Joseph’s Day. The

tale was first spun [7] in the early twentieth century by then Monsignor John O'Sullivan and quickly caught on—the annual Fiesta de las Golondrinas is still celebrated today.

Significantly, Politi recounts the legend through the experiences of latino characters—Julian, the bell-ringer and gardener of the Mission, and Juan a school-age boy.

The return of the Capistrano swallows makes up part of the collective cultural memory of many Americans, mainly because of Leon René’s song “When the Swallows Return to Capistrano,” made famous by the Ink Spots and others. In René’s song, a longing for the swallows’ return is a poetic conceit for a lover’s pining for his sweetheart.

Here's Bobby Day's version of the hit.

But Politi puts an important spin on the story, suggesting that it is because of the hard work and care that Julian and Juan give their garden that the birds return—as the song Politi composed for the story explains: “into my garden they’ll fly to admire my flowers”.

Although Politi presents the California Missions in an uncritical way, he humanizes minority ethnic characters (bilingual ones to boot), giving them agency, thoughtfulness and a sense of history.

Julian worked hard in the gardens, for Saint Joseph’s Day was coming soon. He wanted the gardens to look their best for the swallows’ return.

Politi (1908-1996), nè Atiglio Leoni Politi, was born in the US, raised in both Italy and England, and made a career as an illustrator and children’s book writer in California. Many of his works focus on California border culture, and we can see how he melds aspects of Italian ethnicity with other ethnicities, most notably Mexican American.

Although the study of childen’s literature has long been a sub-discipline of literary studies, a thorough, Italian-American-inflected critical intervention on culture produced for children has yet to be written. Leo Politi, whose words and drawings continue to spark curiosity in young minds, would be a good place to start.