Last month, Diane Di Prima gave an inaugural address as

San Francisco’s fifth poet laureate [2]. In commemoration of International Women’s Day, I celebrate this important Italian American cultural figure, creative writer, and feminist thinker; a woman whose life and work help remind us that U.S. ethnic identity is never static, stale, or flat.

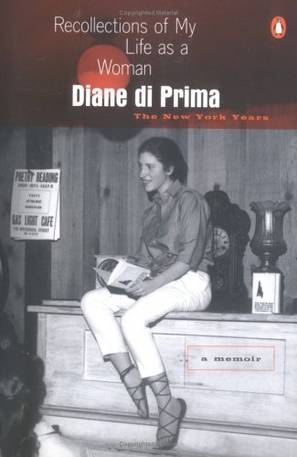

Di Prima, born in Brooklyn in 1934, has lived in Northern California for the last forty-plus years. She’s generally considered the most

prominent woman Beat poet [3] and has always evoked her Italian ethnic identity in her writing. In practically every genre she has practiced, she references her immigrant family’s past and her experience as a woman in an Italian American family.

In it, what starts as a chaste depiction of family celebrations becomes yet another moment to explore her character’s sexual experiences and varying concepts of pleasure. With indirect references to bella figura and the lack of personal space among Italians, she points to just how much context helps communicate (or not) intentionality:

Our feasts and festivals had been hearty peasant affairs, at which, ever since I was twelve, I had found myself dodging the amorous advances of a portly uncle, who was ostensibly teaching me the tango; at which I had had to stand for inspection while my grandmother and my mother’s older sisters felt of my budding breasts, drawing them out with their fingers, or spanned my bottom with their hands, while commenting in Italian on my good and bad points as a future breeding animal. All this was done in a spirit of utter kindness and delight. No one of my thirty-four aunts or uncles had ever been heard to complain of their sex life or marriage—it would have been an inconceivable breach of etiquette—except for unfortunate Aunt Zelda, whose husband had simply left her, and who therefore could no longer pretend to be happy whether she was or not. (pgs. 48-49)

In the spirit of the Beat movement which she helped shape, the piece shows her poetic focus on sexual experimentation, creative expressions of identity, and personal introspection. At the same time, the passage so efficiently lays out her immigrant subjectivity.

Listen and watch Di Prima read the first part of “April Fool Birthday Poem for Grandpa,” about one of her grandfathers, an anarchist from near Formia.

Here the poet links her grandfather’s political workwith his Italian (American) background, but also with contemporary revolutions, contemporary calls for change: “we do it for you, and your ilk, for Carlo Tresca/for Sacco and Vanzetti, without knowing.” the poem continues (beyond what is on the above video clip).

Of course, Di Prima’s oeuvre contains complexities of style, tone, and approach that I am not touching on here. She celebrates female power and the diversity of human experiences with a genuineness that is unambiguously playful. That she also creatively highlights her ethnicity offers us yet another kind of Italian American identity that we can look to, one that is far removed from the stereotypes, clichés, and seemingly boring pancakes (see

John Turturro in the New York Times [6]) too-often associated with Italian American women’s and men’s lived experiences.

Happy International Women’s Day!

-------------------------------

For just a sampling of the academic research on Diane Di Prima’s work, in particular in relation to her Italian American identity, see:

Barbara Kirschenbaum, "Diane Di Prima: Extending La Famiglia," MELUS, 1987.

Roseanne Giannini Quinn, “The Willingness to Speak": Diane di Prima and Italian American feminist body politics” MELUS, 2003.