We called them cugines.

They were the super ginzos, the hyper wops, the swamp guineas. Deep, deep Brooklyn.

We were Italians Americans, too, but different. Or so we wanted to be.

It wasn’t the attention to hair, body, and cars that was troublesome, but an ethnic identity directly linked to a geographically-bounded racism that I found ugly and frightening.

Located in the racially-charged neighborhood

Canarsie [2], South Shore High School during the early 1970s was dictated by circumscribed groupings: blacks and Puerto Ricans over there, whites over there. Within the orbit of white teenagers were further subdivisions. Cugines and JAPS (Jewish American Princesses) were linked in a middle-class, white ethnic style of puffy hair and disco. Freaks were dedicated to the American promise of sex (far too little), drugs (far too much), and rock ‘n’ roll (far too loud).

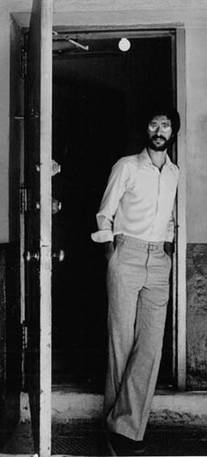

I straddled these different and often conflicting universes: a long-haired, bearded, salsa/disco-dancing Italian-American who desperately sought to escape the confines of my outer borough existence. Tony Manero riding the subway to Manhattan was a cinematic inspiration that helped motivate me to get the hell out.

Cugines morphed into guidos and ended up on the Jersey Shore, and I got a Ph.D.

Of course, that’s too simplistic an ending. My life is significantly more complicated than this truncated telling and so are those of guidos.

As a social scientist trained as an ethnographic folklorist, I have spent the past thirty years researching the expressive cultures of Italian American New Yorkers. I have often interviewed people whom I once labeled and dismissed as guidos, and who subsequently embraced the term as an ethnically-marked youth style.

It is fortunate that sociologist Donald Tricarico has been researching guido culture for over twenty-five years. His work has helped me to understand and appreciate the varied ways expressivity and identity emerge among contemporary Italian-Americans and, in particular, youth. (See the bibliography below).

And then came MTV’s realty show “Jersey Shore.”

When the self-appointed leaders of Italian-Americana did what they do best—become insulted by media projections—it was evident that they were unaware of the existence of Italian-American youth in the northeast who self-ascribed as guidos. For these modern-day prominenti, guido was only an ethnic epithet. Those of us from New York and the metropolitan area familiar with guido culture could only shake our heads in disbelief. Where had these “leaders” been for the past thirty years?

Given this unawareness, I proposed that the Calandra Institute invite Prof. Tricarico of Queensboro Community College (City University of New York) to present his research on guido culture. He, in turn, suggested inviting Johnny De Carlo, a northern New Jersey caterer and a self-professed guido, with whom he communicated online to the academic colloquium.

“Founder and chairman of the Bowling Green Association” Arthur Piccolo hurled a rambling invective against Prof. Tricarico (the originally posted insult “MORON” has been changed to “IDIOT”), Distinguished Professor Fred Gardaphé of Queens College, and the Calandra Institute in

his i-italy.us blog post [3]. Piccolo’s vituperation against “so called ‘intellectuals’” states: “When in spite of their degrees and their titles they are nothing but dumb or worse traitors for a few pieces of silver thrown at them for pissing on their own community.” Such a repugnant display of anti-intellectualism is more frightening than anything I ever experienced among the cugines of South Shore High!

The January 21st colloquium “

Guido: An Italian-American Youth Style [4]” does not “glorify” guidos any more than our lectures, readings, film screenings, and conferences have endorsed the mafia,

fascism [5], anarchism,

religion [6],

Neapolitan music [7], neo-burlesque, or the other varied subjects presented at the Institute. Many of these self-professed leaders have never or rarely attended the Calandra Institute’s free public events. They were notably absent from the Calandra Institute’s 2007 conference “

Recent Scholarship on Contemporary Italian-American Youth [8]” which featured Prof. Tricarico’s research on guidos. (I would be remiss not to mention that the National Italian American Foundation has supported Calandra Institute with several generous grants.)

The appalling anti-intellectual reaction to the Calandra Institute colloquium raises some basic yet critical issues. What is Italian-American culture(s)? How is Italian-American identity reproduced? Who speaks for Italian Americans?

Anthropologist

Fredrik Barth [9] observed that ethnicity is a performance of difference displayed at the boundaries between groups. Ethnic borderlands are in constant flux, shifting from generation to generation, from moment to moment. Context is everything.

In addition, the “cultural stuff” that signifies italianità in the United States is constantly changing, yet a sense of Italian identity prevails. Being Italian American is not contingent on dancing the tarantella, eating spaghetti, or even speaking Italian. Hair gel or

a dinner gala [10], in concert with other objects and behaviors, have come to signify “Italian” in certain contexts in what Prof. Tricarico has called “a dynamic, adaptive character of ethnicity.” Under what conditions does one object or activity become privileged over another as an expression of Italian-American identity?

Scholars have pointed out that Italian-American elites emerged as “power brokers,” ethnic mediators between the mass of Italian Americans and mainstream American society. They served in this capacity by becoming arbitrators of what constitutes italianità. These prominenti historically devalued folk and vernacular expressions, promoting elite cultural forms like opera and establishing a pantheon of revered “ethnic heroes” like Columbus (see Harney 1993). Key to this work of cultural politics is the issue of “authenticity.” What constitutes “real” Italian culture and “real” Italians?” (I hope to address Italian nationals’ beliefs on this subject in a future post.) An

annual gala dinner [10] is no more an “authentic” expression of Italianness than hair gel, or, for that matter, speaking standard Italian. Individuals use these and other culturally-charged key symbols to collectively shape meaning and create value as part of the varied expressions of Italian-American cultures and identities.

The Italian-American elite had and continues to have a vested political interest in shaping and policing cultural expressions and ethnic identity. The late historian Philip Cannistraro, Distinguished Professor at Queens College and interim director of the Calandra Institute, noted:

Throughout the Italian American experience, the prominenti have consistently endorsed a closely-linked agenda of “patriotism” and Americanization, which has essentially meant supporting the coercive efforts of American society designed to strip Italian immigrants and their descendants of their history, culture, and their identity. The dual focus of prominentismo has always been to promote the separate, self-aggrandizing interests of their own particular elite rather than of the community as a whole, and to stress what Italian Americans are not.

Cannistraro’s historical assessment helps us put the most recent “controversy” concerning guidos in perspective: In whose interest is it to attack media representations, Italian-American youth, and stifle intellectual inquiry? Not mine.

Bibliography

Harney, Robert F. “Caboto and Other Parentela: The Uses of the Italian Canadian Past.” From the Shores of Hardship: Italians in Canada. Essays by Robert F. Harney. Nicholas De Maria Harney, Ed. (Welland, Ontario: Éditions Soleil, 1993), 4-27.

Tricarico, Donald. “Read All About It!: Representations of Italian Americans in the Print Media in Response to the Bensonhurst Racial Killing.”

Notable Selections in Race and Ethnicity [13]. David V. Baker and Adalberto Aguirre, Jr., Ed.. (Sources, June 2001), 291-319.

Tricarico, Donald. “Dressing Italian Americans for the Spectacle: What Difference Does Guido Perform?”

The Men’s Fashion Reader [15]. Andrew Reilly and Sarah Cosbey, Ed. (New York: Fairchild, 2008), 265-278.