I’m a

Netflix subscriber [2], of course, but I still on occasion rent from Berkeley’s best video store,

Reel Video. [3] Walking around its labyrinth of DVDs is similar to strolling around the stacks of a good library. It’s a surefire way to come across titles that will keep you dreaming of holing up in a hotel room in Sardinia in the middle of winter with nothing to do but watch movies.

And so it was at Reel last week that I came across a newly released series from Sony,

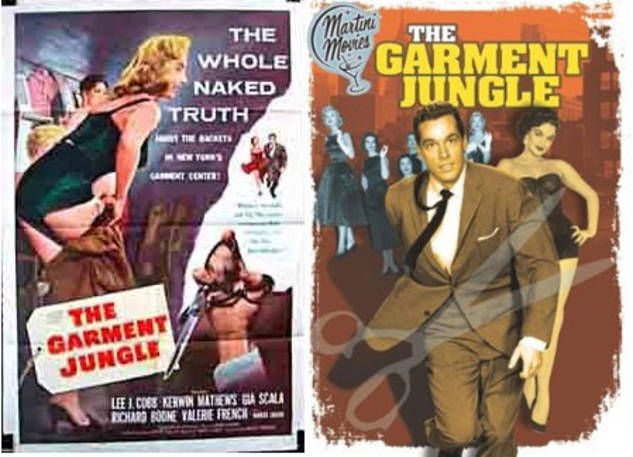

“Martini Movies;” [4] films that according to the box copy are “hip and iconic films for the cool film lover.” I’m not really sure what that means—to me they just seemed like B movies on a crime theme. I was drawn to all of them, but most of all to 1957’s

The Garment Jungle [5] (directed by Vincent Sherman), which promised to bring together Italian Americans and labor in the shape of a noir.

The opening credits state that the film was based on a series of “articles” without any more explanation. A couple of email exchanges with Tom Zaniello of Northern Kentucy University (author of

Working Stiffs, Union Maids, Reds, and Riffraff [6] and

The Cinema of Globalization [7]) led me to at least one of the articles the screenplay was based on:

Lester Velie’s [8] “Gangsters in the Dress Business” from Readers’s Digest, July 1955. (The original trailer,

linked here [9], calls attention to the featherweight American magazine as a way to establish the film’s journalistic credibility.)

A series of Velie’s articles—Red Scare-era all the way—were collected in Labor U.S.A. Today (first published in 1958), a book my husband brought home at my request from Oakland’s Laney College Library, where it hadn’t been checked out since 1973. In Velie’s chapter “The Boys from Seventh Avenue,” in a section called “Garment Jungle,” he outlines the different ways in which (mostly Italian American) “hoodlums” violently attempt to keep the garment industry non-unionized, mainly by coercing sweatshop owners, blackmailing and threatening union organizers.

And it is here that Velie outlines the 1949 murder of William Lurye, a union activist in the garment industry who was brutally murdered by union-busting (mostly) Italian American organized crime figures. As a cultural critic, I’m fascinated at how this real historical event gets reinterpreted on screen. Sherman’s film relocates the Italian American identity of the original gangsters to the union organizers themselves.

Of note is a character by the name of Tulio Renata (played by a young

Robert Loggia [10]), who more or less depicts the real-life Lurye. He’s written basically as a garment workers’ version of

Pete Panto [11]!

Our sympathies lie completely with Tulio, not only because he’s on the side of the workers, but because he’s got a likeable wife, Teresa (played by

Gia Scala [12], neè Giovanna Scoglio), and a young baby, Maria.

The image of this young, Italian American, politically progressive family, was for me the best part of the film. Their relationship is touching and warm, even as Teresa has to negotiate at times Tulio’s all-too-typical (Italian American) machismo. They have an understanding about each other’s needs: we see him caring for the baby while she’s working (teaching dancing!), and we hear her characterize his commitment to the cause: “He’s not in it for himself, but to help others,” she tells the sympathetic son of a garment industry boss.

Formally the film is straight-forward, nothing fancy. The box’s description of it as a noir is somewhat misleading, I think. It has no femme fatale, no fatalistic private detective, only a gritty underworld and questionable morality. Instead, it shares much with other great U.S. labor films from the 1950s, most conspicuously with two 1954 films:

On the Waterfront [13] and

Salt of the Earth [14]. Both were filmed on location, whereas the majority of The Garment Jungle was shot on a Columbia sound stage. One notable exception is the use of stock footage, presumably from Lurye’s funeral with thousands of garment workers in attendance, to depict Tulio’s public funeral. (Check out a description of Lurye’s funeral in

Fighting for the Union Label [15] by Kenneth C. Wolensky, Nicole H. Wolensky, and Robert P. Wolensky).

Cinema images of Italian Americans who are strong, courageous, and compelling--and not members of the mob or solely carried by the weight of stereotypes--are rare. They seem to pop up in unexpected places--like in the aisles of a hoary institution like a library or a video store.