“Polentoni” have Fared no Better than “Terroni”

His answer is neither a direct response to Pino Aprile, author of the controversial book Terroni, nor is it a northern manifesto against the South. He makes this clear right from the start.

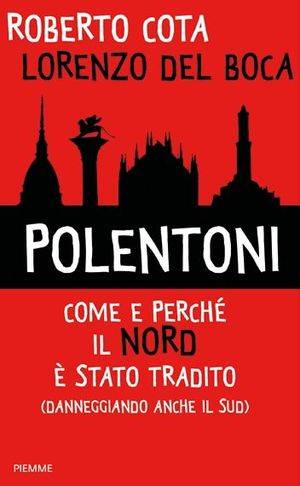

Without claiming any undue credit, I wrote Maledetti Savoia in 1996 and Indietro Savoia in 1999. This was a dozen years before Pino Aprile who, moreover, quotes me extensively as a bibliographic reference.” Del Boca, author of Polentoni, is referring to the book that is often juxtaposed alongside his: Terroni by Pino Aprile. Both books will be presented and discussed by the authors themselves at an event organized by ILICA. The debate will be moderated by Prof. Anthony J. Tamburri, Dean of the Calandra Institute.

We asked him to tell us what we can expect, to summarize in a few words his work on Polentoni.

I have documented how the South has been stripped, robbed, and massacred. At the base of the Tronto River (which marked the northern boundary of the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies), there were stationed 60 battalions of riflemen who treated the inhabitants as people to be conquered. The freedom they were supposed to bring about was the ideological screen that was used to make the aggression look expendable in the eyes of Europe. They said that the liberators would help to free their brothers. In reality, freedom brought them face to face with the barrel of a bayonet, and in the end, it “liberated” people who did not want to be freed. It was a shameful page in history but after this massacre and dispossession, no one won anything. At least not the people of the north.

And why do you maintain that the North has fared the worst?

The farmers in the Po Valley found themselves in an area devastated by armies that fought each other. First they attacked the Austrians, then the Austrians fought against Piedmont. The “dream” of Savoy that began in 1848 ended (in the north) in 1866 after three wars of independence and a vast number of battles. How many farmers starved to death because their crops were destroyed just as they were about to be harvested?

The Venetians and the Veneto fought the Austrians. They were the sailors who defeated the Italians at Lissa, but the next day they discovered that they were part of another state. They were paying 11 liras a year to the government in Vienna which was efficient by definition, and then they found themselves paying 32 liras to Turin without the benefit of public works being carried out.

These facts and figures show that national resources were just wasted away. Have we advanced at all?

Since then, a number of “initiatives” were taken to help the country’s economy take off, especially in the South which had morphed into “the Southern question.” A ton of money was spent with little to show for it. They paid manufacturers to transfer factories to the South but that did not work. They didn’t produce any jobs but they did produce wages. Alfa Sud, the steel mills of Taranto, companies like Pomigliano d’Arco, Termini Imerese, and various programs such as the “Cassa del Mezzogiorno” [Fund for the South] have proved to be a failure. A very expensive failure.

You maintain that it created a great sense of disappointment...

Yes, the unification of Italy, as it occurred, no longer pleased anyone, not even those who brought it about. In 1867, Giuseppe Garibaldi wrote from Caprera: “I do not regret anything, but I can no longer return to the South for fear that I will be stoned because of the pain that I caused there.”

The same Garibaldini who apparently believed in the Risorgimento were very disappointed. Some – a few – made the best of a bad situation and supported the new state by wearing the uniforms of commanding officers or grabbing a seat in parliament. But for others – the majority – it ended very badly. They were marginalized, shunned, went mad, committed suicide. The most dramatic case was Giovanni Cerutti from Pavia. He woke up before dawn, kissed his wife and daughter who were still in bed, and covered his head with a towel. He then put a nail on his forehead and implanted it in his skull with a hammer. He had just written a line on a piece of paper: “This is not the Italy for which I have risked my life.” A skewed exclamation point was barely covered by a drop of blood.

The 150th anniversary of the unification of Italy is a good time to rewrite, or better, to finally write the history of our country.

To learn more and to meet the authors

Terroni e Polentoni

Pino Aprile and Lorenzo Del Boca

Thursday, November 10, 2011

2:00–7:00 p.m.

St. John’s University – Manhattan Campus

101 Murray Street

Saval Auditorium

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.