Welcome Back to the Future

What was the future like in 1909? The world had changed as never before, or so it seemed.

There were no precedents. Imagine if you can the way the future looked to the best minds in turn-of-the-century Europe. Imagine if you can the sudden impact of the Industrial Revolution of the 1880s.

Imagine the heart-stopping, world-changing mechanical inventions at the time, just like our world-changing inventions today.

What did the future look like to Filippo Tommaso Marinetti in 1909 Paris? What did it look like for the Italian artists, poets, architects, cooks and expats in Paris, Milan and Turin? Yes, the world had changed as never before, or so it seemed. There were no precedents, no paradigms to study. The past was slow and teary-eyed; the present, an electric jolt.

They were troubling and confusing times. You could look backward and embrace the sweet and melancholy 1800s, the 1879 of Vienna, or the Romantic world of the early and mid 19th century. You could be swayed by the rhyme of sentimental poetry, swept up in the insistently rich orchestrations of Brahms or return to relive Beethoven’s peasants dancing in a ring far from the city as a storm approaches.

Or you could return to the inevitably tragic view of love embodied by Goethe’s Werther or the

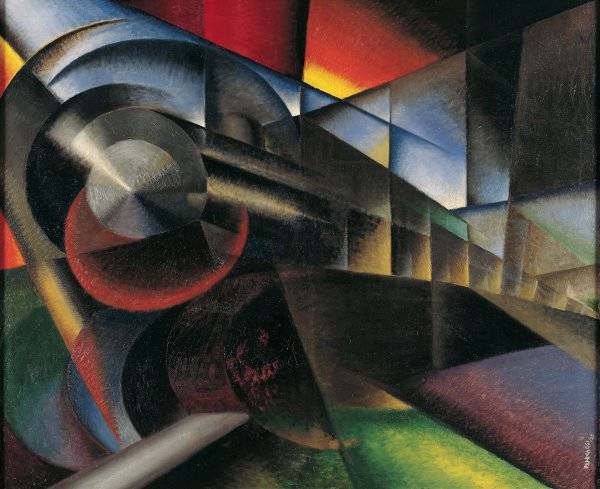

plight of Byron’s prisoner of Chillon. Or, you could accept the noise, the sound, the friction and the dynamism of a new century, of a post-industrial revolution world where screeching noises, the palpable friction of steel running on rails, the persistent smoke puffing from a chimney 75 feet tall, or the thrill of commanding a horseless carriage at 25 miles per hour with a foot pedal. You could accept it and embrace it, let it permeate your new 20th century sensibility as you rode off with a bang, not a whimper. You could open your soul and make it one with the new mechanistic order of things. You could see a future for expression that matched the future of life in the new interdependent, fast, steely, two-lanes-ahead world.

A revaluation of all values

Into this milieu came a movement that declared itself a revaluation of values. In the 1880s no less a figure than Nietzsche, living between Italy, Switzerland and Germany, called for exactly that: a revaluation of all values. Other philosophers, poets and artists followed suit, as the antique drum faded and a new sound emerged. And the Italians were, as usual, among the first to champion a new order in art, a “now” movement that wholly embraced the shimmering body of the industrial revolution.

Marinetti and his followers cried, Make war. Exult in bombs. Turn the impersonality of this world into a structure for art, architecture, music, food and every part of life. They looked ahead to the inevitable remaking of society and its worldview.

Futurism was born as a modus vivendi, a way of living and seeing and hearing. The art

hanging on the walls of the museums seemed “lifeless” to them, vague and sentimental

relics. Futurists found master works selfindulgent, decadent, unresponsive to the evolving new order—the same way, I suppose, a young person today might see newspapers or printed books or sea voyaging in the age of the Concorde.

Industry and conflict, war and speed

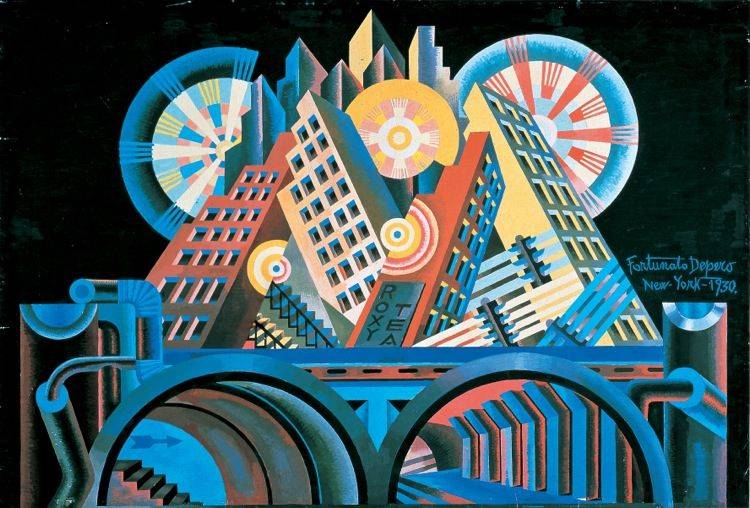

Think of it. In 1909 an art of speed, beautiful machinery, the combustion and friction of life in cities, endless smoke and unprecedented noise was engulfing artists looking at their easels or blank pages trying to divine a form or message. Italian Futurists managed to swim in the unexplored current, not drowning, but paddling toward the new shore of the real.

They reviled critics, labeling them embalmers whose “corpses” glorified the old world of manners and refinements, of sentimental love and idleness. They wanted the world to be infected with the germs of industry and conflict, war and speed, violence and danger, and they worked to spread a new sense of dis-ease borne by machine energy and power.

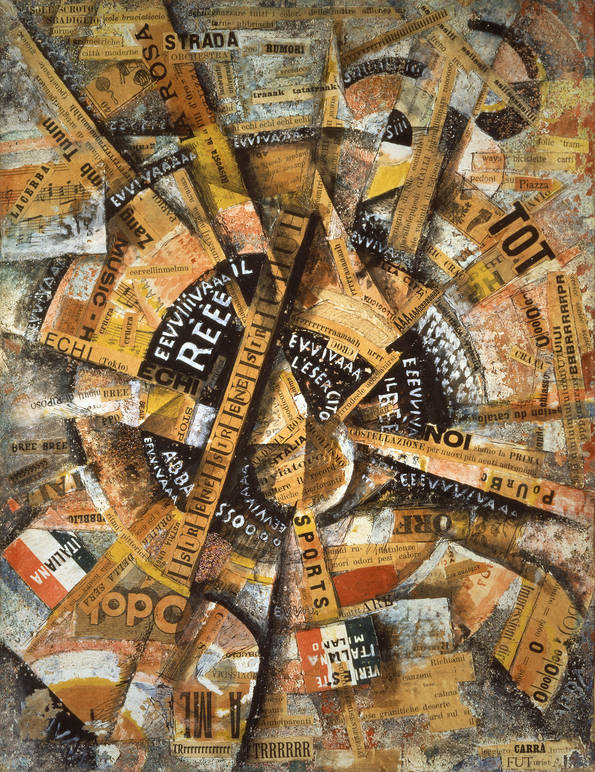

Their paintings would defy the confines of the canvas with blaring onomatopoeia. They wanted the scope and dimension of their paintings and sculptures to issue sound and energy. They glorified social disturbance, light rays emitted from a street lamp, the swish of a dog on its leash, the forward surge of a train.

In the music of Pratella, which would have been pure cacophony to Liszt or Mozart, they played for audiences the sounds of the days and nights of the new age, with instruments made from cans or pipes, or played in unusual ways to simulate the squeaking of wheels on a railroad track or the painful whirr of a factory machine.

Unlike sentimental artists or academics, the Futurists would have relished it, if, in the middle of an interview, one’s cell phone went off loudly or if a play were interrupted by shouts of protest or praise. They didn’t see such things as interruptions, but as complements to an experience.

The present of Futurism

The movement hasn’t quite ended. Today, even graffiti takes its iconoclastic place in a Futurist world. It is highly self-expressive. It is full of bold colors. It is not the stuff of museums. It is fresh to some and irritating to others. We find hints of futurism in architecture, music, industrial design, art, film and even cooking.

Futurists loved demonstrations. They would find this article boring because it contains no noise, no surprise blasts, no color, no violence. Please don’t tear up this page! But do think about it! Ah, there are cars passing outside, but I can only refer to them. Planes pass overhead and a bus stops and resumes on its way. Maybe I should end this trifling essay with a whoosh, erk, erk, thump, and whaaaaaa!!!!!

To Futurists, the present does not simply reject the past. It embraces the inevitable future, the technology that they believed would transform the world. And has. Zoom.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.