Week of the Titans

Between Sunday, April 10, and the following Sunday, April 17, a remarkable number of concerts ended with the public going wild and giving the performers well deserved standing ovations and endless rounds of applause. The recipients of these waves of love and approval were two of the greatest active conductors, James Levine and Riccardo Muti, both of whom have recently seen their activities seriously threatened by health problems.

On April 10, Levine led his Met Orchestra at Carnegie Hall in a performance

of Schoenberg's Five Pieces for Orchestra, Brahms' Symphony No. 2, and Chopin's Piano Concerto No. 1, featuring the Russian pianist Evgeny Kissin. The great conductor, who will turn 68 in June, had recently made the papers for having left his position of Music Director of the Boston Symphony Orchestra and having delegated almost 50% of his Met engagements to others, owing to health problems.

On Sunday he needed a walker to cross the stage and a cane to climb up on the podium. But when he set those items aside and wielded his baton, it was as if nothing were wrong. The execution of Schoenberg's Op. 16 from 1909 was unbelievable. The piece was written in the composer's intermediate phase between his tonal and 12-tone periods, and Levine did a masterly job in expressing the melodic freedom of the work, dragging the captivated audience along in its sudden bursts of fortissimi and spine-chilling pianissimi.

The big star of the evening, though, was the 40-year-old Russian virtuoso Evgeny Kissin, who enthralled the public with a breath-taking execution of Chopin's first Piano Concerto, written at the age of 19. In perfect symbiosis with the orchestra, Kissin offered an unforgettable example of how to tackle the Polish composer's early works with strength and dynamic range. Maybe too much so, one might argue, considering Chopin's reputation as weak and quiet, delicately performing his fast and complicated passages on pianos that did not yet have cast-iron innards. After a long standing ovation, the pianist treated the public with a solo encore, Chopin's B-flat minor Scherzo, Op. 31.

Back in their natural habitat, at the Metropolitan Opera, Levine and his orchestra performed a run of Berg's first opera, Wozzeck, reprising a 1997 production by Mark Lamos and featuring the amazing baritone Alan Held in the title role. Making it sound really easy, Levine unraveled the intricate score for the audience with precision and expression, helped by the Weimar-esque sets and lighting and an ideal cast that also included Waltraud Meier as Wozzeck's companion Marie, Walter Fink as the Doctor, and tenors Gerhard Siegel and Stuart Skelton as the Captain and Drum Major, respectively.

Also, Levine was preparing for a run of performances of Wagner's Die Walküre, in Robert Lepage's new production, which opened on Friday, April 22.

Meanwhile, back at Carnegie Hall, the long-awaited three-day

visit of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra, led by their new Music Director, Riccardo Muti, was taking place. Muti, who will turn 70 in July, was forced to bow out of his first month of residency due to exhaustion, and when he finally returned to Chicago in the winter for three weeks of concerts, he collapsed on the podium during a rehearsal, which resulted in multiple fractures to his jaw and cheekbone and prompted doctors to install a pacemaker. Considering his complete rehabilitation and his triumphant return to success, as well as a youthful choice of “pure energy” repertoire, a joke is circulating involving the Maestro asking his doctors to set the pacemaker on “High”.

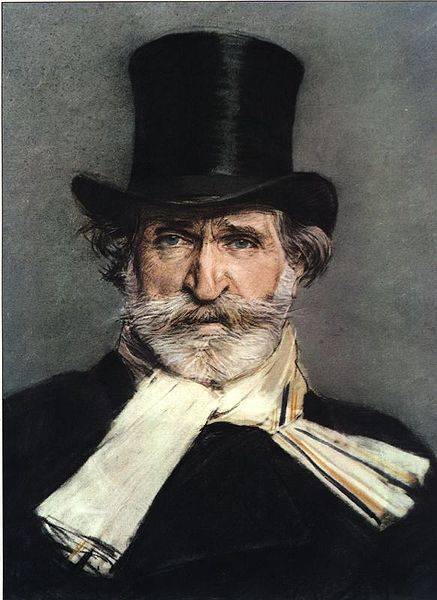

The ailments seemed completely consigned to the past when Muti charged to the podium, smiling, amid the cheering of the audience on his first night at Carnegie Hall, on Friday, April 15, to perform one of Verdi's masterpieces, his second-last opera, Otello.

The hall was completely sold out. The stage was overloaded by the large orchestra, the Chicaco Symphony Chorus, the Chicago Children's Choir, and a cast of singers that included the excellent Latvian tenor Aleksandrs Antonenko in the title role, veteran Carlo Guelfi as the evil and cunning Iago, and an amazing Krassimira Stoyanova as the innocent Desdemona, who delivered an unforgettable performance that outshined her colleagues.

From the opening orchestral explosion it was clear to all the listeners that this was going to be a real treat. Like Verdi’s Messa da Requiem (1874), Otello is as much a choral work as a straight opera, and this allows it to be experienced at its fullest even in a concert performance, in the same way that one could experience Beethoven's Ninth Symphony or Berlioz's Damnation of Faust. Verdi puts everything into the music: movement, feeling, chaos and madness. One wants to seek cover during the sublime storm and battle that opens the opera, just as clearly as one wants to peek out from the previous shelter when the clouds have dissipated in the second half of Act I, and witness the tender exchange between Othello and Desdemona.

But as much as Verdi has put into this indescribably beautiful

work, it takes an expert to extract the hidden nuances that are necessary to grasp the full potential of its drama. There is no conductor alive better than Riccardo Muti at this task. Italian opera is his domain and Verdi is his stronghold. Nobody present at the performance will ever be able to forget it.

The clarity and passion the CSO expressed on Friday night reverberated throughout the following two concerts and, personally, Otello kept looping in my mind while attending Saturday's performance of Berlioz's Symphonie fantastique and Lélio.

Moving back in time from Otello, the harmonically revolutionary character of Berlioz's symphony – which he wrote in 1830, at age 27 – was almost muffled, but the execution certainly was not. Muti is also a great Berlioz interpreter, and he knows how to get the right sound from the orchestra. Lélio, a fairly boring composition, creates a somewhat anti-climactic juxtaposition with the symphony, but Muti likes to perform the two works consecutively, as Berlioz wished. In recent years, he has done this with the help of the most famous French actor alive, Gérard Depardieu, who offered an entertaining reading of the text, written by the composer himself, albeit with a strong Shakespearean influence.

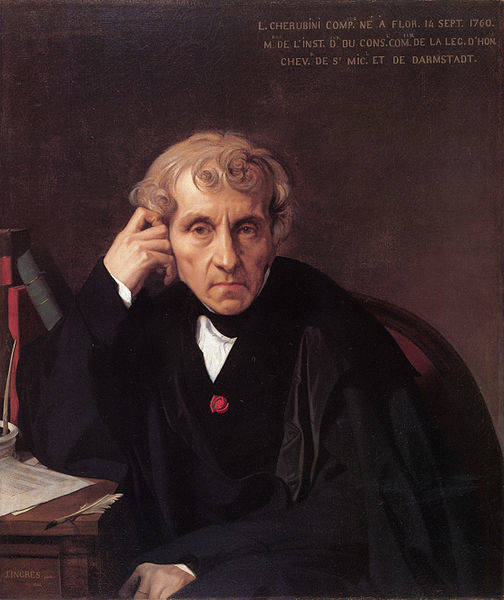

The final concert – the least unusual of the three - took place on Sunday afternoon and featured Cherubini's Overture in G Major, Liszt's Les Préludes, and Shostakovich's Symphony No. 5. It was originally supposed to have featured a work by Varèse and a new piece commissioned by the CSO, but that program had to be skipped by the conductor during his rehabilitation. A rarely performed work, Cherubini’s overture was the real treat of the program, especially since Cherubini is another Muti specialty.

In conclusion, every week of classical music in New York is a special week, and that is what makes the city the musical capital that it is. But sometimes there are peaks. Carnegie Hall boasts the best acoustics in the city and among the best in the country and beyond, and by hosting these two great conductors who have recently reminded us of their own mortality and human frailty in general, it gifted us with a little extra slice of temporary infinity.

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.