Addio, Cosimo

Cosimo Matassa, who died September 11 at age 88, was a son of Sicilian immigrants to New Orleans who, like so many of their connazionali, settled in a working-class, multiethnic French Quarter neighborhood. Matassa became a pivotal figure in American vernacular music through his role in creating “the New Orleans sound” in his recording studios. According to music historian Jeff Hannusch, “Virtually every rhythm and blues record made in New Orleans between the late 1940s and early 1970s was engineered by Cosimo Matassa, and recorded in one of his four studios.” Matassa made hit records with many renowned African American artists, including Fats Domino, Dave Bartholomew, Big Joe Turner, Roy Brown, Little Richard, Irma Thomas, Lee Dorsey, Aaron Neville, Smiley Lewis, Guitar Slim, Ernie K. Doe, Lloyd Price, Clarence “Frogman” Henry and Roy “Professor Longhair” Byrd.

Matassa collaborated with some of New Orleans’ best musical minds, including the bandleaderand arranger Dave Bartholomew, whom Matassa called his best friend; pianist, songwriter, and arranger Allen Toussaint; the drummer Earl Palmer, who invented the rock ‘n roll backbeat; pianists Huey “Piano” Smith, James Booker, and Mac “Dr. John” Rebennack, and the saxophonists Lee Allen, Herb Hardesty and Alvin “Red” Taylor.

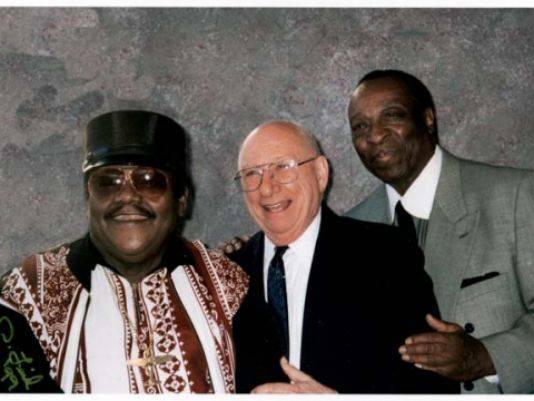

The night before Matassa died in a New Orleans hospital after a long illness, Toussaint and Bartholomew were at his bedside to say their farewells to "Cos," their longtime friend and collaborator. "Cosimo was the doorway and window to the world for us musicians in New Orleans," Allen Toussaint told the New Orleans Picayune. "An expert, with a lot of heart and soul. When the Beatles heard Fats Domino, they heard him via Cosimo Matassa. He touched the whole world."

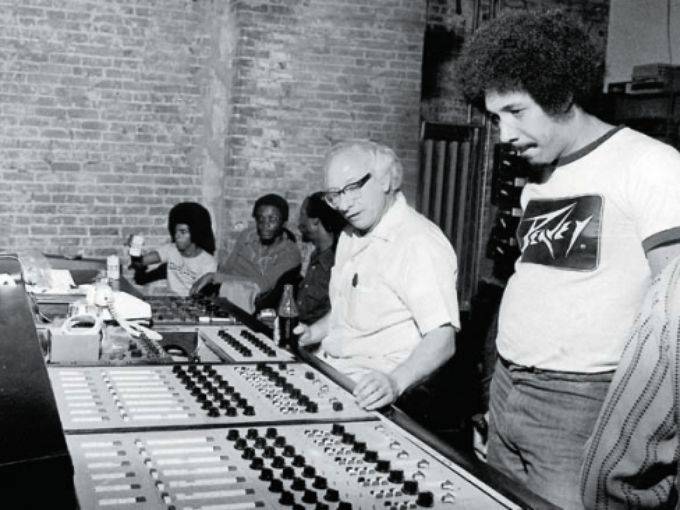

Matassa wasn't a musician, and he always was modest about his role in the creation and development of the New Orleans sound. He told interviewers that he was a “facilitator” who strove to “get the performance and the performer on the tape with the least interference and the least resistance.” But his contributions far exceeded that. “Cosimo built the institution where we musicians all had to go through. It was our university. We all came through Cosimo,” said Toussaint. In his biography, Backbeat, Earl Palmer, recalling the early days of his work with Matassa, said, “I think Cosimo was a genius. I’ve seen engineers use two dozen mikes to get the sound he got with three. He knew how to position mikes and he knew each mike like it was a person.”

Challenging Racial Barriers

But Matassa wasn’t only a recording engineer, studio owner, and producer. He also was a cultural broker who introduced African American artists, marginalized by music industry and societal racism, to a broader audience. Matassa didn’t consciously aim to challenge racial barriers. “We didn’t intentionally seek out black artists in those days,” he said. “I grew up in the French Quarter where blacks and whites lived side by side. We didn’t have black neighbors or white neighbors; they were just neighbors. We were integrated -- we just didn't know it.”

According to jazz scholar Bruce Boyd Raeburn, Matassa was “among those who grew up in New Orleans and responded to the cultural opportunities that the environment provided. In his case, as in so many others, the process of attraction to black culture was a result of his daily experiences in the neighborhood where he grew up.”

In other American cities where African Americans and Italian Americans were in close proximity, there have been conflicts, sometimes violent, between the two communities. But Cosimo Matassa remembers the French Quarter as a neighborhood where blacks and Italians (the latter predominantly Sicilians) lived “cheek by jowl” and even shared traditions, such as St. Joseph’s Day celebrations.

Matassa was aware that his association with African American recording artists did not endear him to “respectable” white society. “The uptown folks thought of me as the ‘nigger studio,’” he recalled. “Even though I did people like Pete Fountain and Al Hirt, what stuck was that I worked with blacks. The studio was never in the newspapers, there were no tea dansants for me. An Italian was kind of an outcast down there, too.”

Cosimo Matassa’s life and career represent an aspect of New Orleans history that has yet to receive its full due: the role of Sicilian immigrants and their descendants in shaping the Crescent City’s unique and celebrated culture. Like the popular entertainer Louis Prima, Cosimo Matassa was born in New Orleans to Sicilian immigrants and grew up in the French Quarter. Matassa’s father, Giovanni Cosimo Matassa, emigrated from Cefalu, Sicily in 1910; his mother, Domenica Leto, had arrived earlier, from Palermo.

When Matassa was growing up, the French Quarter was full of music. His uncle, Vincent Matassa, was a clarinetist who played in New Orleans Italian brass bands. His mother’s family was even more musically inclined; her sister Cicetta played piano in what Cosimo calls their family band; Cicetta’s husband, Joseph Di Guardi, was the band’s clarinetist. “I came up hearing the mazurkas, polkas and schottisches and marches," he recalled in a 1993 interview. "And of course I also heard them because in those days the jazz bands on the streets played them a lot more than they do now.”

In 1924, Matassa’s father bought a grocery store at the corner of Dauphine and St. Phillip streets. The senior Matassa, by then known as John, also owned a saloon. There young Cosimo first heard commercial music on his father’s jukeboxes. He also was exposed to racial segregation, since his father’s saloon actually was two establishments, one for whites, and one for blacks.

“His arrangement was unique,” Cosimo recalled. “The wall between them had an arch big enough for a wide door and they built a phone booth in that. So the telephone was accessible to either one. There was a door on each side of the phone booth. Imagine a phone booth with a door on each side. That’s the way it was. And it was a jukebox in the white bar and it was a jukebox in the black bar. So I got to hear country tunes, blues tunes, the whole thing. I was hearing what black people listened to and what working class white people listened to at the same time.”

After graduating from high school, Matassa went to Tulane University to study chemistry. But after two years, he decided that field wasn’t for him. He went to work for a jukebox company, J&M Amusement Service, which his father co-owned. He also enrolled in the Gulf Radio School for several months, where he learned “basic electronic circuitry,” enabling him to repair jukeboxes. In 1945, the company, renamed the J&M Music Shop, and the building that housed it extensively renovated, began selling new and used records, home phonographs and radios.

Making Musical History

A small backroom in the J&M Music Shop became Cosimo’s first recording studio. Earl Palmer recalled that the studio “was hardly bigger than a bedroom. Everyone faced Cos, who was in the little bitty booth. Cos never had an assistant; he came in and out and set them mikes himself.”

One of Matassa’s first recordings was “Pizza Pie Boogie,” a novelty tune by New Orleans jazz trumpeter Joseph “Sharkey” Bonano and his Kings of Dixieland.

In 1947, singer Roy Brown recorded "Good Rockin' Tonight," the song that popularized the term "rockin,'" at J&M Studios. Two years later, on December 10, 1949, a twenty-one-year-old Antoine "Fats" Domino cut eight songs in J&M's tiny back room, including his first single, "The Fat Man." The record reached number one on the Rhythm and Blues charts, launching both Domino’s career and what has come to be called “the golden age” of New Orleans R&B. In 1956, Matassa relocated his studio to 523 Governor Nicholls Street; two years later, he moved the studio to 525 Governor Nicholls when a building at that address, formerly a cold-storage warehouse, became available.

During the late 1950s and early 1960s, the hits just kept rolling out of Matassa’s studio – “Tutti Frutti,” “Lucille,” “Good Golly Miss Molly,” “Long Tall Sally” and “Slippin’ and Slidin’” by Little Richard; “Lawdy Miss Clawdy” by Lloyd Price; “Ain’t Got No Home” and “I’m a Country Boy” by Clarence “Frogman” Henry; “I Hear You Knocking” by Smiley Lewis; “My Blue Heaven” and “I’m in Love Again” by Fats Domino; “The Things That I Used to Do” by Guitar Slim; “Tipitina” by Professor Longhair; “It’s Raining’ by Irma Thomas; “Rockin’ Pneumonia and the Boogie Woogie Flu” by Huey “Piano” Smith; “Ya Ya” and “Working in the Coal Mine” by Lee Dorsey; “Sea Cruise” by Frankie Ford; “Tell it Like it Is” by Aaron Neville, and many more.

The British label Proper Records has released two, four-disk boxed sets of Matassa’s recordings, The Cosimo Matassa Story, (2007), and The Cosimo Matassa Story Vol. 2 (2012). The two compilations total 229 recordings, and although not every track is first-rate, even the lesser ones are full of the exuberant spirit and rhythmic excitement that characterized “classic” New Orleans rhythm and blues and rock ‘n roll. Not only that – The Beatles, the Rolling Stones and other British rock groups covered songs recorded in Matassa’s studios, so, as Allen Tousssaint observed, his work also influenced the 1960's British Invasion.

Matassa relocated his studio once again in the mid-60's, to Camp Street. But by this time, popular tastes were changing. The last major national hits to come from Matassa’s studio all were recorded in 1966 – Lee Dorsey’s “Workin’ in the Coal Mine,” Robert Parker’s “Barefootin’” and Aaron Neville’s “Tell it Like it Is.” Several independent record labels that had recorded at Matassa’s studios went bankrupt and couldn’t pay for their sessions, and New Orleans banks refused to make loans to Matassa. The IRS eventually confiscated his studio for nonpayment of taxes and auctioned off the equipment.

As that unfortunate outcome makes evident, Cosimo Matassa did not get rich from his work as a studio owner and recording engineer. He estimated, in fact, that he lost more than $200,000 over the years. Bruce Boyd Raeburn observes, “Cosimo never got the backing he needed locally to capitalize on the hits he produced, so they had to be licensed elsewhere for distribution, which meant the big money also went elsewhere. Local bankers were not about to invest in collaborations between Sicilians and blacks.”

Retirement and Recognition

Matassa continued to work as a recording engineer at Sea Saint Studio, owned and operated by his friend Allen Toussaint and Marshall Sehorn. He retired from music and, in the 1980s, returned to the grocery business. In 1999, fifty years after Fats Domino recorded “The Fat Man,” Matassa’s studio at Rampart and Dumaine streets was declared a historic landmark. Today, it is a laundromat, but photographs lining the walls commemorate the building’s storied history as the foundry from which emerged so many hits that would change the course of American popular music.

In recent years, Matassa received more of the recognition his accomplishments merited. In 2007, he was inducted into the Louisiana Music Hall of Fame and received a Grammy Trustees Award from The Recording Academy. The following year, the Italian Cultural Institute of Los Angeles honored him with its Lifetime Achievement Award, in a ceremony held in New Orleans's Piazza d’Italia. In 2012, he was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and received its Award for Musical Excellence.

Bruce Boyd Raeburn agrees with Matassa’s description of himself as a “facilitator.” “He wasn’t musical himself,” says Raeburn. “But he loved to fiddle with gadgets and he was attracted to black music. He ‘produced’ by creating a place where black musicians like Professor Longhair and Earl Palmer and Little Richard could do their thing, and he was willing to put in the time, money and ingenuity to experiment until they found the sound they were all looking for."

"Without him, the history of American popular music would look very different.”

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.