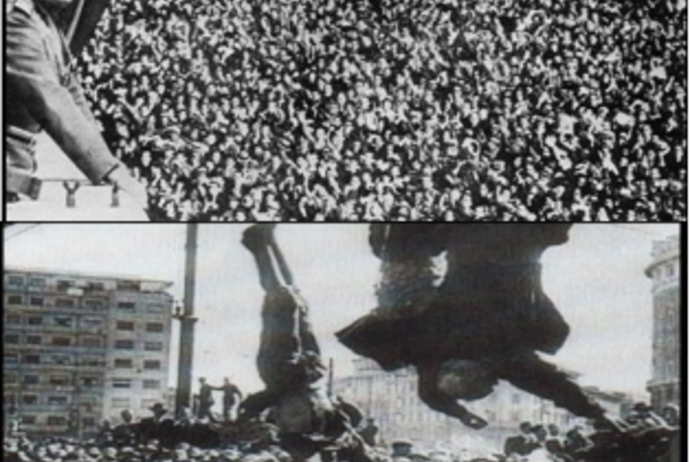

AP Victory !

...corks popping, faces beaming, toasting, embracing

...Spirit of southern masses looks on smiling, thinking:

...naiveté, hubris

...how many celebrations 2,500 years - nay more

...another Lingua Franca

...another pretender to the throne of southern culture

...sense of history lacks

...put the corks back

...Piedmontese as others will leave

...taking Tuscan dialect back

...where it should be

/////

Lingue Franche

“Speech”, renowned classical scholar, linguist and world historian Arnold J. Toynbee posits:

“grows out of the need for communication between equals who are bound together by common interests and by a regulated system of intercourse.”

(A Study of History v.1 p.174 n.1)

When one society comes to dominate another through war and/or commerce, there arises a need for a common language (speech) to facilitate “communication between [people] who are bound together by common interests and by a regulated system of intercourse.”

Thus, for example, when the Piedmontese militarily conquered and commercially dominated southern Italy and Sicily beginning in 1860, there arose a need for a common language understood by both the Piedmontese and the people south of Rome. Such languages imposed for purpose of communication between diverse linguistic societies are called Lingue Franche (singular: Lingua Franca).

Very often the lingua franca imposed by the dominating society is the mother tongue of that society. For example, English, the mother tongue of Britain, was the lingua franca of the British Empire; i.e. English was the language of government, commerce and university education in all the Empire countries.

However, historically there are examples of the dominating country imposing a lingua franca not of its own mother tongue. Thus, for example, the Piedmontese selected the Tuscan dialect for the lingua franca to be used in all its Italian dominions, even though Tuscan was not the mother tongue of Piedmont.

Tuscan – Mediterranean Lingua Franca

Centuries before the Piedmontese conquest of Italy, Tuscan was functioning as the lingua franca for much of northern Italy, and beyond into the Levant. Toynbee writes:

“In the so-called 'medieval' period of Western history, we see the Tuscan dialect of Italian eclipsing its rivals and at the same time being propagated round all the shores of the Mediterranean by Venetian and Genoese seamen and traders and empire-builders, as well as by Pisans and Florentines who spoke Tuscan as their mother-tongue...”

(Study v.5 p.502)

Later, long after the Italian city state zenith, Tuscan still prevailed as a lingua franca around the Mediterranean. Toynbee:

“This Pan-Mediterranean currency of the Italian language in its Tuscan shape outlived the prosperity, and even the independence, of the medieval Italian city-states.

"In the sixteenth century Italian [Tuscan] was the service language of an Ottoman Navy that was then fast driving its Venetian and Genoese opponents out of Levantine waters...

“In the nineteenth century, again, the same Italian [Tuscan] was the service language of a Hapsburg Navy whose Imperial-Royal masters were successful from 1814 to 1859 in reducing Italy herself to the mere 'geographical expression' that Metternich had pronounced her to be.

“In fact the Osmanlis and the Hapsburgs each in turn found themselves constrained to employ an Italian [Tuscan] medium of communication as an indispensable element for the purpose of holding the Italian people in check; and thus the Italian [Tuscan] language succeeded twice over in forcing itself down the throats of strangers who were so far from speaking it by nature that they were actually the mortal enemies of the people who had inherited it as their mother-tongue.

(Study v.5 p.502)

Tuscan –Lingua Franca of Italy

Clearly, when the Piedmontese set their course to bring the whole of Italy under their control; realizing that they would need a universal language to unite all the diverse regional languages, Tuscan was an obvious choice.

Choice is the operative concept here; for Tuscan was not the mother tongue of the Piedmont. Denis Mack Smith writes:

“The Piedmont, which emerged as a nucleus around which the rest of Italy could gather was one with no great tradition of italianità. It was a partly French-speaking area, which straddled the Alps and had existed only on the borderline of Italian history.

“The House of Savoy, which lead the Italian revolution, was until the eighteenth century centered on the French and Swiss side of the mountains.

“There was no exclusive feeling for Italy in Savoy’s almost French rulers. Cavour, Mazzini, and Garibaldi were born subjects of France, and Napoleon's sister stood godmother at Cavour's christening. (Italy: Modern History p. 17-18 emp.+)

Indeed, the complete lack of understanding of the language that would become the national language of Italy on the part of the leaders of Italian unification is stunning. The first seven elections to the position of Prime Minster were shared by five men that had to be taught Italian[Tuscan]. Smith:

"Like Garibaldi, Cavour had an imperfect knowledge of Italian, and he preferred to write in French. Other people had to revise his newspaper articles, and his secretary found it painful to hear him speak Italian in public.

Until quite lately, the Italian language had been unacceptable in Turin society and Cavour was not untypical in being more at home in French literature and English history than in Italian... General Lamarmora was one of the last Italian statesmen to have to learn Italian almost as a new language. (Modern History p.20)

Nevertheless, Tuscan was the French-esque Piedmontese lingua franca of choice, and it became the national language of Italy. The point here is the ostensibly arbitrary almost capricious way, through the force of arms, by which southern Italians and Sicilians came to speak Tuscan through no choice of their own.

Class Character of Lingue Franche

Again, Toynbee’s stipulation above:

“Speech grows out of the need for communication between equals who are bound together by common interests and by a regulated system of intercourse.” (emp. +)

His comprehensive study of all the various examples of lingue franche in world history clearly indicates their class character.

“Equals with common interest” is virtually a definition of a political-economic class.

Consider for example, the imposition of English lingua franca in British Raj India and its very obvious class character. Toynbee:

“In 1829 the British Indian Government made English the medium for its diplomatic correspondence, and in 1835 the medium for higher education in its dominions.

But, in the conduct of judicial and fiscal proceedings...local vernaculars were used.” (Study v.7 p.243 emp. +)

Clearly, there is a class distinction in what constitutes the standard language. Government and higher education used English, and the masses (“the great unwashed”) spoke in the vernacular.

Tuscan class character in Sicily

One can find no better example of the class character of lingue franche than the complete failure of Tuscan to penetrate the peasant class of Sicily almost 100 years (five generations) after it was imposed on the institutions of government, commerce and education. Luchio Visconti’s 1948 film La terra trema exemplifies this failure.

In 1948, Luchino Visconti adapted Giovanni Verga’s I Malavoglia, bringing the story to a modern film setting. The resulting film, La terra trema (The Earth Trembles), starred only non-professional actors and was filmed in the same village (Aci Trezza) as the novel was set in.

Because the local dialect differed so much from the Italian spoken in Romeand the other major cities, the film had to be subtitled even in its domestic release.

Clearly, the masses of Sicilians knew nothing of the Tuscan lingua franca.

Tuscan lingua franca Today

After the 1950’s the advent of mass media radio, television, film etc, and the increased levels of public education in the South, Tuscan increasingly penetrated the masses. However, its victory is still limited and, if the past is a guide to the future, may be ephemeral.

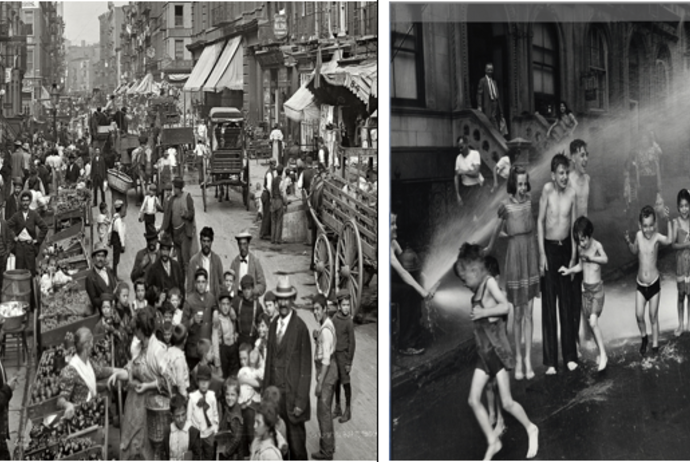

Even today, after generations of post war compulsory education, where children are forced to learn the alien lingua franca Tuscan dialect, and the dialect is exclusively used by media, and in the bourgeoisie and literati institutions; the languages of the South are still prevalent and seemingly thriving.

In their introduction to a fascinating collection of essays Italian Cultural Studies: An Introduction, David Forgacs and Robert Lumley observe:

“Italy has remained uniquely plurilingual, with...very large number of 'ItaloRomance' dialects which are still used by many speakers (often now in alternation with one or other of the many regional and social varieties of Italian).” (p.14 emp.+)

Tullio de Mauro, one of the essayists writes:

“The 'Italian dialects' -- which are very strongly differentiated and very viable, being used, even today, by more than 60 per cent of the population and, in fact, being used exclusively, that is, not alternating with Italian or another language, by 14 per cent of the population” (p. 95 emp.+)

Tuscan in southern-Italian Americana

As noted above, lingue franche are always a class phenomena. The foreign military and commercial dominating culture imposes the lingua franca of choice; and an all too willing bourgeoisie and literati, recognizing the realpolitik implications for wealth and careers embrace it. However, the masses continue to use the native tongue.

In America, the southern Italian languages were struck a mortal blow during WW II by the government’s “Don’t Speak the Language of the Enemy” propaganda program. Italy was the enemy; therefore, we should not speak our native languages.

However, even this mass propaganda program could not have succeed if the Italian American literati did not embrace it with a passionate fervor. After the war they devoted themselves to exclusively teaching the language, history and culture of northern renaissance Italy. One could not find and still cannot find courses let alone degrees in the languages, history and culture of southern Italy and Sicily. (This is to say: if one takes a random sample of all the Italian courses and degrees offered in the American higher education system since WW II, the probability of finding a course or a degree in southern-Italianita offered is close enough to zero to treat it as such.)

The Italian American literati have fully embraced the language and corresponding culture of Dante, rejecting the languages and culture of Naples and Aci Trezza, although they love to indulge nostalgic reminiscing about their southern nonni.

Orientalism in southern-Italian Americana

Accordingly, the progeny of southern Italy in American schools today have no teachers - no one to teach them the language, history and culture of their forefathers.

But, they can get college credits if they pass the AP Tuscan exams!