.

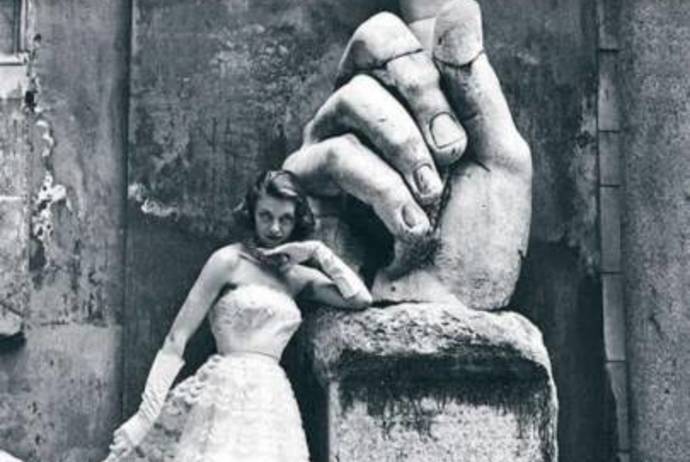

Quando Roma era un Paradiso (When Rome Was a Paradise), a 2016 Strega Prize nominee, is a collection of author and painter Stefano Malatesta’s memories from his youth in post-World-War-II Rome when the Eternal City unseated Paris as Europe's center of artistic and intellectual activity.

The book's title, taken from a quote by American artist Cy Twombly, refers to the rise of the international film industry at Rome’s Cinecittà studios, a period known as Hollywood sul Tevere (Hollywood on the Tiber), and the art industries that flourished alongside it. According to Malatesta, Rome in the 1950s and 60s seemed like “an immense trattoria” with a “continuous party” atmosphere (occasionally Felliniesque in nature) that was frequented not only by directors, actors, writers, artists, and athletes, but also by those who profited from them, honestly and otherwise.

The result is a fascinating glimpse of some of Rome’s legendary cineasti (filmmakers), cinematografari (second-rate filmmakers), fettucinari (fettuccine-makers) and falsari (counterfeiters), among others, and the language that they inspired.

NEOLOGISMS

In addition to l’arte dell’arrangiarsi (the art of getting by) and vitellone (literally, a calf; figuratively, a slacker), Malatesta cites two neologisms created in Rome during the post-war years.

paraculo (literally, for ass; figuratively, opportunist)

“Paraculo” venga dalle imbottiture dei calzoni che le mamme previdenti preparavano ai loro figlioli, ragazzini di quattordici anni e già distinti ladruncoli, specializzati nel furto con salto.

(“Paraculo” comes from the stuffed trousers that shrewd mothers made for their sons, boys around fourteen years of age and already distinguished petty thieves who specialized in theft by jumping.)

cinematografaro (second-rate filmmaker)

Il termine era nato nel dopoguerra insieme a vitelloni e paraculi e stava a indicare la gente del cinema senza una qualifica precisa, personaggi illetterati e rozzi per la maggior parte, l’esatto opposto dei cineasti.

(The term was born in the post-war period along with vitelloni and paraculi, and it referred to people in cinema without any specific credentials, for the most part ignorant and uncouth characters, the exact opposite of the cineasti [filmmakers].)

BORROWINGS

Due in part to the influence of the likes of Orson Welles, Truman Capote, and Audrey Hepburn, American English became fashionable throughout Italy, resulting in the use of intact and Italianized terms that persist in present-day usage.

hollywoodiano (adjective for Hollywood)

Nell’estate del ’45 era uscita un film che rivoluzionava i modi del fare il cinema, dopo aver gettato via i valori del sistema hollywoodiano già contestati da Orson Welles.

(In the summer of ’45 a film came out that revolutionized the ways of making cinema, after having thrown out the values of the Hollywood system, which had already been contested by Orson Welles.)

American way of life

Come il Settecento è stato il secolo della Francia, l’Ottocento dell’Inghilterra, così il Novecento è stato il secolo degli Stati Uniti e nessun paese in Europa è stato così influenzato dall’American way of life come l’Italia in quegli anni.

(Like the eighteenth century was the century of France [and] the nineteenth of England, so the twentieth century was the century of the United States, and no country in Europe was more influenced by the American way of life than Italy in those years.)

happening

Una delle sere più divertenti a cui Matta aveva partecipato appena arrivato a Roma, era stato un happening intitolato “serata anti-clericale”, una festa assolutamente goliardica, organizzata da Consagra il 20 settembre del 1949 per ricordare la breccia di porta Pia.

(One of the more entertaining evenings that [the painter] Matta participated in as soon as he arrived un Rome was a happening called “Anti-Clerical Evening,” an absolutely goliardic party organized by [Pietro] Consagra on September 20, 1949, to commemorate the bombardment of Porta Pia.)

ROMANESCO and “AMERICANO”

The Americanization of Italians in this period was satirized in the 1954 film “Un Americano a Roma (An American in Rome)” with Alberto Sordi’s character, Nando Mericoni, who speaks in a mix of Romanesco, Italian, and “American.”

Nun annà a destra perché c'è er burone daa Maranella, o'right? o’right!

(Non andare a destra perché c’è il burrone della Maranella, va bene? Va bene!) (Italian)

(Don’t go right because the Maranella ravine is there, all right? All right!)

“LATIN”

Following the success of the film "Quo vadis?," the influx of Americans turned Rome into a giant Circus Maximus, with local business owners, in particular restaurateurs, capitalizing on the appeal of ancient Rome, a fact which gave new life to so-called “Latin.”

taberne (an Italianization of the Latin tabernae; single-room shops in ancient Rome)

Romani te salutant (a non-existent phrase; English: Romans salute you)

Se uno andava sull’Appia Antica trovava i ristoranti battezzati con i nomi “taberne”, dove il proprietario si affacciava all’entrata vestito da centurione dicendo una frase che in Latino non esiste “Romani te salutant”, probabilmente copiata da “Morituri te salutant.”

(If you went to the Appian Way you would find restaurants baptized “taberne,” where the owner stood at the entrance dressed as a Centurion saying a sentence that doesn’t exist in Latin, Romani te salutant, probably taken from Morituri te salutant [those who are about to die salute you].)

CUISINE

Restaurant owners also capitalized on the success of the film industry by renaming local dishes after famous movie stars.

tripa ar sugo Aldo Fabrizi (tripe with Aldo Fabrizi sauce)

‘na cofana de bucatini alla rozza Magnani-Rossellini (a bucket of bucatini with rude sauce Magnani-Rossellini-style, named after Anna Magnani and Roberto Rossellini)

Pajata Anitona (calf intestines Anitona-style, inspired by Federico Fellini’s affectionate nickname for Anita Eckberg, Anton [Big Anita])

E noi rispondiamo co’ “la trippa ar sugo Aldo Fabrizi”, con “’na cofana de bucatini alla rozza Magnani-Rossellini”, che ricordano un noto episodio dell’aneddotica di Cinecittà, con la “Pajata Anitona,” dei bei tempi della “Dolce Vita.”

(And we respond with “tripe with Aldo Fabrizi sauce,” with “a bucket of bucatini with rude sauce Magnani-Rossellini-style,” that recalls a notable episode in the anecdotage of Cinecittà, [and] with “calf intestines Anitona-style,” from the good times of “La Dolce Vita.”)

But Italians don't really seem to like these translations, and the debate is still open. On one side, there are those who support the introduction of foreign words, especially English words, into the Italian language, considering them as a way to show off a more international and sophisticated culture. On the other side, many linguists believe that the overuse of these words could represent a threat to the purity of the language.

But Italians don't really seem to like these translations, and the debate is still open. On one side, there are those who support the introduction of foreign words, especially English words, into the Italian language, considering them as a way to show off a more international and sophisticated culture. On the other side, many linguists believe that the overuse of these words could represent a threat to the purity of the language.