The Mysterious Case of 315 Johns

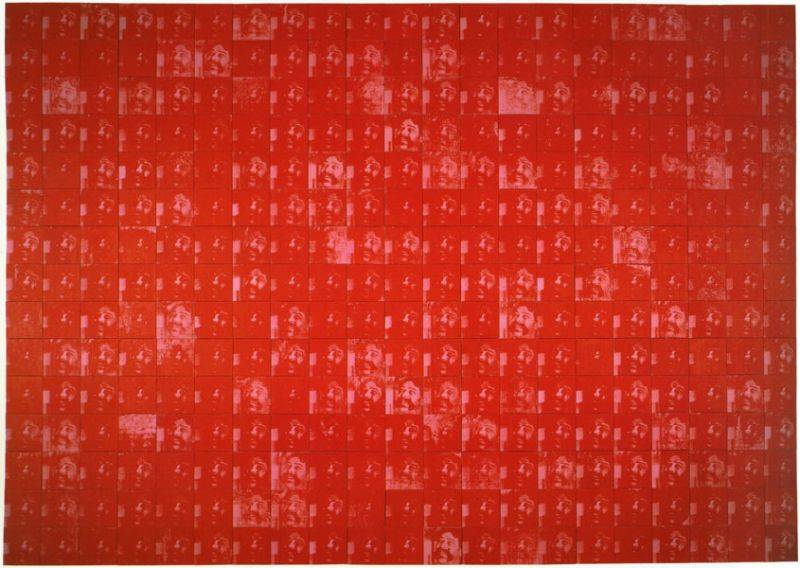

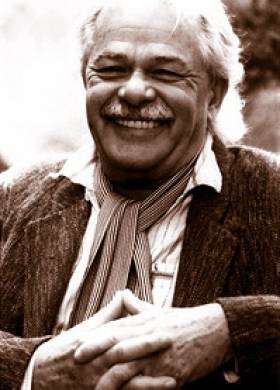

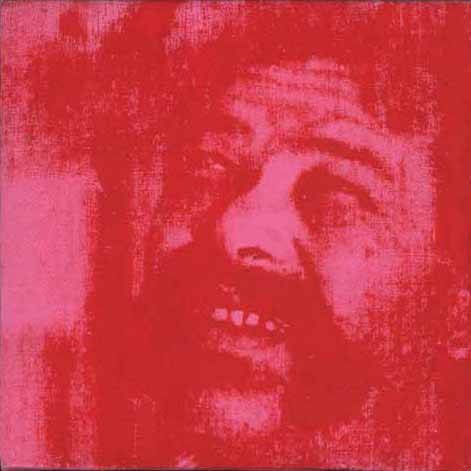

The work of art “315 Johns” is at the center of a legal battle involving Mr. Gerard Malanga, photographer and former collaborator of Andy Warhol, and the famous sculptor Mr. John Chamberlain. The picture, composed of 315 canvases portraying Mr. Chamberlain, has been sold by him in person for 5 million dollars, after he had authenticated it as an Andy Warhol.

Mr Malanga claims to be the co-author of the work of art, the other one being Jim Jakers, photographer and former assistant to Mr. Chamberlain. In 2005, as soon as he knew that the painting had been sold as a Warhol for such a significant price, he bought his partner’s share and sued Mr. Chamberlain.

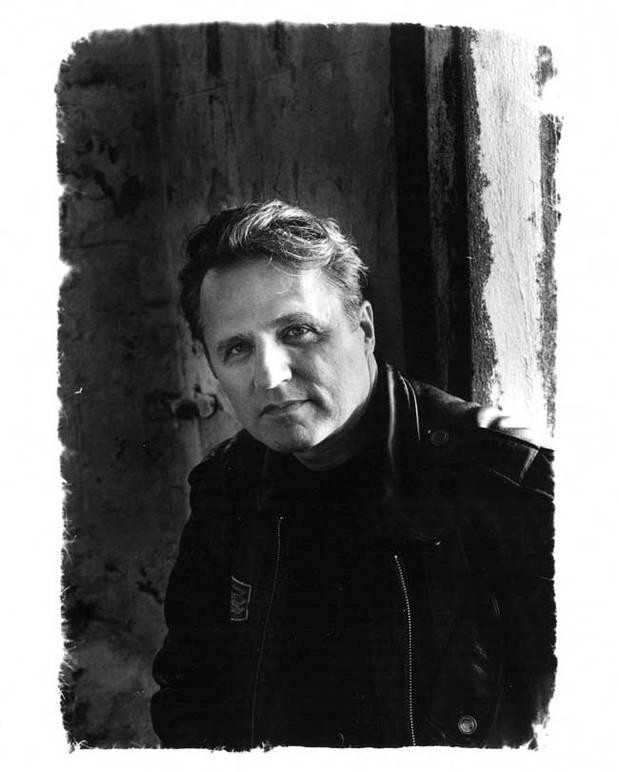

i-Italy met the Italian-American artist Gerard Malanga and asked him to tell its readers his version of the facts.

“When I last saw ‘315 Johns’ it was just an unfinished piece, one on which my partner Jim and I still had to do some work. It was our first project together and Jim wanted to pay tribute to his maestro John Chamberlain by making a portrait of him. We came up with 320 8-inch square canvases, each one representing John in different positions, with different colors and slightly different techniques. We didn’t want to use all of them: we would have rejected most of them and used just 80 or 100. We stored them in Jim’s studio in Massachusetts, the same place were we met to work on the project in 1972. When Jim moved to New York in 1975 he brought the pieces to his studio in Manhattan but then, in 1977, when he moved again, he gave some of his stuff to Mr. Chamberlain. Among these things were the paintings that were kept in his studio. From that moment on, both Jim and I lost track of the work of art, and didn’t think about it anymore ….we simply trusted John Chamberlain and thought that they would remain there where we left them”.

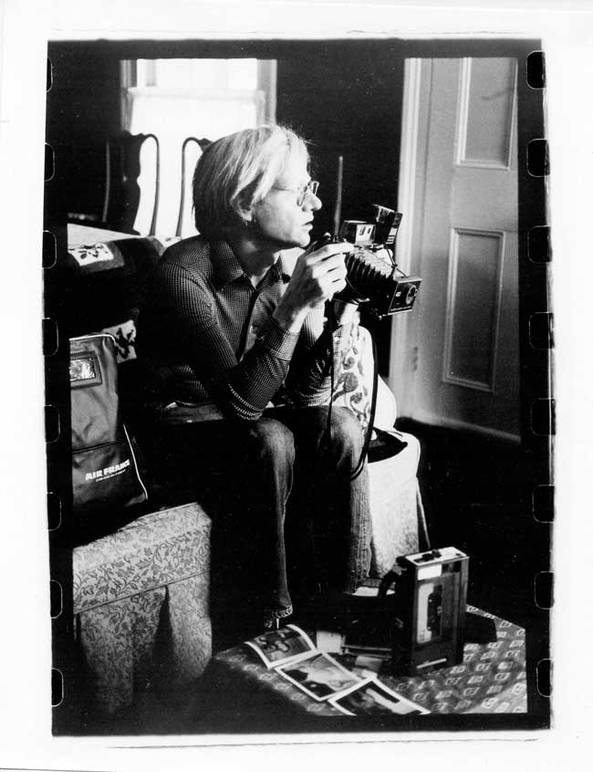

The 1970s were great years for Gerard, who started his own career as a photographer in 1971, after having been assistant to Andy Warhol for several years.

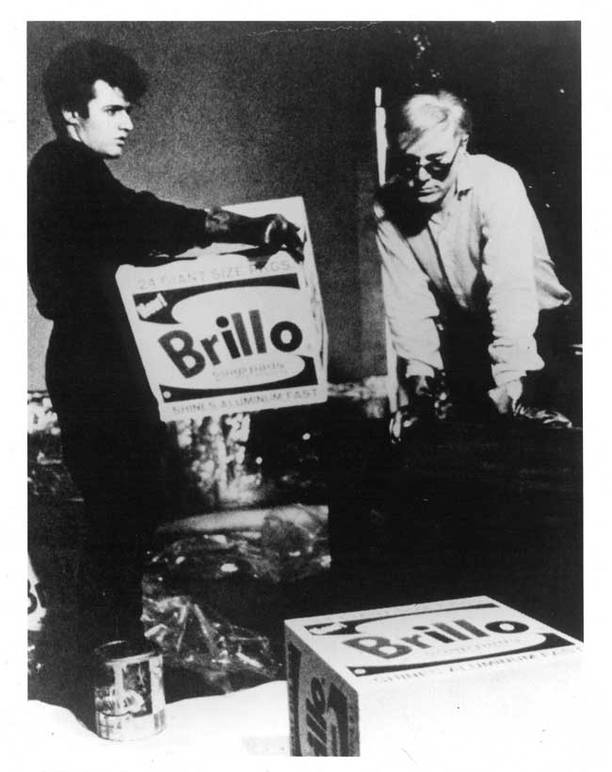

During all those years he learned his techniques, and collaborated with him on several projects, some of which became very well known to the great public: “Among them, the most famous are probably the Elvis Presley portrait and the Elizabeth Taylor Silver portrait. Together we did all his flower paintings and the “twelve most wanted men” that we showed in Paris in 1964. The last painting we worked together on was a portrait of Dominque De Menil”.

Gerard always remembered the tricks of the trade he learned from Andy, and maintained a strong relationship with him ever after. It was Andy, in fact, that really gave him the necessary help and backing to start his career when he was only a college student, “I started working with Andy in June 1963, when I was in college. A very close friend of mine knew that I had previous experience in the art field, and he also knew that Andy was looking for an assistant since he was working o very big paintings that required a lot of work. So my friend, Charles, arranged a meeting between Andy and myself on a Sunday. The first thing Andy said was ‘When can you come and work for me?’ So I went to his studio the next Tuesday, on June 11, 1963. To me this was a summer job. I wanted to go back to school in September. But then Andy asked me to come to Los Angeles for the opening of an exhibition we had been working on during the summer. At first I kind of hesitated because I felt guilty about abandoning school. I thought, I could leave school for a semester…but I never went back!"

From that time on Gerard pursued his dream to become an artist and then a photographer, a dream that very few Italian-American at that time could dare have given the very poor conditions many of them lived in. Indeed, this was Gerard’s case too. Thus he always recognized the great fortune he had had, and became a faithful friend and collaborator of Andy as long as he lived: “I am the only child of two Italian parents. My father came to the United States from a village outside of Potenza and my mother was born here but her own parents were Italian, from Salerno. I grew up in the Bronx and I lived in very poor circumstances…my parents were not rich at all. So whatever I did in my life, I did it through my imagination and my curiosity for life. Although I was very determined, I was always respectful and honest with my colleagues. Mr. Chamberlain, on the other hand, seems to have forgotten the meaning of these values”.

When Gerard met Mr. Chamberlain in February 2004 he found out that he had sold the painting: “I met Mr. Chamberlain at the opening of an annual art exhibition organized by ‘The Art Dealers Association of America’ on Park Avenue. I hadn’t seen him for at least 15 or more years, so I went to greet him and ask him how he was. As we were talking somehow he changed the subject and said: “You know that painting you made of me? I sold it for 5 million dollars.” I though he was joking! I remained in a slight state of shock when I heard it because it brought back memories…. Then you know what happened? Six weeks later I was having dinner with Jim and he confirmed everything! He had met Chamberlain a month before I did and was told the same news. So obviously this was not a joke… That’s when I decided to buy Jim’s shares of the work of art and sue”.

The legal action is still just at the beginning, as Justice Martin Schneier rejected a summary judgment motion presented by Mr. Chamberlain, as well as his evidences in their entirety.

“Mr. Chamberlain’s version can be easily proven as completely false. He claims that in 1968 he made an art trade with Mr. Warhol in exchange for one of his sculptures called 'Jackpot'. According to him, a broker by the name of Mr. Godfeller followed the whole transaction. All of this is a total lie for two reasons: the painting was made in December 1971, in 1968 it did not exist; the sculpture Jackpot was already in Andy Warhol’s house in 1962. So there was no trade, at least not in 1968. How convenient of Mr. Chamberlain to say such a thing since both Mr. Godfeller and Mr. Warhol are both deceased and cannot bear witness or defend themselves….”

According to Gerard, Mr. Chamberlain deliberately cheated the Andy Warhol Authentication Board by taking advantage of the popularity he enjoys: “In 2000, John Chamberlain submitted the painting to the Andy Warhol Authentication Board without one piece of evidence to prove that he is telling the truth. They took his word for true because of his notoriety and I refuse to be his doormat! This is the first time that something like this happens in the history of modern art. He is risking his career and popularity with this story, having become a criminal with no credibility at all. There are so many ethical and moral questions involved in this story…”

Not only does Gerard aims to prove that Mr. Chamberlain’s statements are false, but he is also intent on finding his painting, the new owner of which is still unknown: “We still don’t know where the painting is. The person who bought it is involved in a very serious criminal investigation and must show up. He not only bought a stolen work of art, but he bought a work of art that was sold to him as a Warhol. So he bought a forgery. This person must know what is going on here. What bothers me the most is that Mr. Chamberlain still claims that he does not remember the name of the person to whom he sold the painting! This is not possible: any artist must remember the buyer of the works he sells, especially if they are worth millions of dollars!”

The suit has been widely watched by the art world, and has already caught the attention of the media. In an article which appeared in The New York Times on June 26, 2008, the lawsuit was defined as ‘a window onto the convoluted world of post-Warhol Warholiana(...) The case also serves as a primer of the New York art world in the late 1960s and early ’70s, when Warhol was a presiding deity (…)’.

This case interested i-Italy not only because Gerard is an Italian-American; but mostly because we believe our readers have the right to be informed about a story where business oversteps the world of art. “315 Johns” risks being misattributed to the detriment of our art-passionate readers.

Can you imagine if you took your children to a museum and you saw a painting on the wall that was considered an Andy Warhol and it wasn’t?

i-Italy

Facebook

Google+

This work may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, without prior written permission.

Questo lavoro non può essere riprodotto, in tutto o in parte, senza permesso scritto.